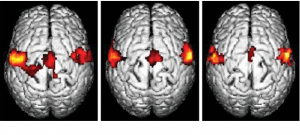

Phantom pain–pain experienced after limb amputation– used to be understood as something “in your head” but now it is recognized as real; fMRIs have shown that peripheral and central nervous system changes occur which cause this pain. The brain image on the left shows how the person with phantom pain has a greater amount of their brain lit up than the control on the right. Phantom organ pain, pain from the removal of an organ, occurs as well.

Phantom pain–pain experienced after limb amputation– used to be understood as something “in your head” but now it is recognized as real; fMRIs have shown that peripheral and central nervous system changes occur which cause this pain. The brain image on the left shows how the person with phantom pain has a greater amount of their brain lit up than the control on the right. Phantom organ pain, pain from the removal of an organ, occurs as well.

Excerpts from Remnant of My Heart

Stephanie Zimmerman, MSN** wrote a blog post, “Remnant of My Heart” which refers to her own experience of phantom organ pain. Here is an excerpt from the post.

“My body ‘thinks’ that my heart is still there even though it isn’t. My heart died April 21, 2008. My phantom pain is not so much pain as it is an ache: intermittent and unpredictable. I’ve come to befriend it as a sweet, tender reminder of my native heart.

In the days immediately following my transplant, I slowly emerged from layers of sedation and paralytics and I began to grieve. I grieved for my donor, her death saving my life. I also grieved the death of my heart, the heart a-flutter on my wedding day, the heart that lulled our son to sleep in utero, the heart I’d known my entire life.

Ayn Rand’s description of a great oak in Atlas Shrugged best captures the impact of the death of my heart on me.

“Eddie Willers, aged seven, liked to come and look at that tree. It had stood there for hundreds of years, and he

thought it would always stand there… He felt safe in the oak tree’s presence… it was his greatest symbol of strength.

One night, lightning struck the oak tree. Eddie saw it the next morning. It lay broken in half, and he looked into its trunk as into the mouth of a black tunnel. The trunk was only an empty shell; its heart had rotted away long ago; there was nothing inside…. The living power had gone, and the shape it left had not been able to stand without it.”

I had always felt safe in the presence of my heart; I trusted my heart implicitly. I was confident in its ability to sustain my life despite the chemotherapy and chest radiation I’d received as a child. Even though my heart sustained damage, never once did I think that my ‘greatest symbol of strength’ would be shaken, uprooted, split it half, devoid of ‘living power.’

The question that loomed large for me in the early years after my transplant was, would the “shape left,” the person, be able ‘to stand without” its heart?

The reality was that part of me died. The grief didn’t come in a series of ordered stages. No. It was an unrelenting hot mess: one-step forward, two-steps back.

Our son was instrumental in my healing process. I slowly stepped back into my role as his mom and realized that he is my heart. The grief has subsided though the phantom pain comes and goes. And with it I remember and am forever thankful to my donor and her family who made watching him grow up possible.”

**Stephanie has been a frequent guest author. Her story can be found at After Cancer Treatment, Living Out the Cure as well as The Gift of Organ Donation: Honoring Donors and their Families. She has also contributed posts on self-advocacy as a patient: How Do I Advocate For Myselfand Open Letter to Healthcare Providers.

Stephanie also writes at Living the Cure.