It’s getting difficult to ignore the research…there’s a world of bacteria, archaea*, eukaryotes** and viruses partying away on and in your body. Actually, this microbiome, as it is called in the scientific community, is involved in our health in ways we never dreamed of before.

It’s getting difficult to ignore the research…there’s a world of bacteria, archaea*, eukaryotes** and viruses partying away on and in your body. Actually, this microbiome, as it is called in the scientific community, is involved in our health in ways we never dreamed of before.

Commensalism and Symbiosis

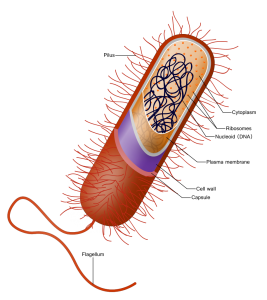

In fact, the tissues where these microbes live are the same places where pathogenic microbes enter the body–the skin, the lungs and the gut. The relationship that is in place between this microbiome and humans is called commensal. Commensalism is a term describing the relationship between two organisms, one that benefits from the relationship and the other which is neither harmed nor necessarily benefiting from the relationship.

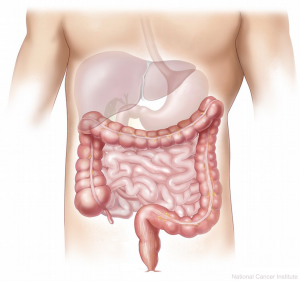

In the human gut lives a complex ecosystem with as many as 100,000,000,000,000 (10 to the 14th power) microorganisms. Humans provide these microbes with safety, stability and food. The microbes help our bodies digest food, create vitamins, defend against pathogens and even teach our immune system.

Immune System and Microbes

Termed “the immune system – microbiota alliance,” the immune system’s education starts at birth. It is thought that prior to birth, the fetus is germ free–has no microbes in the gut. At and after birth, exposure occurs to microbiota of the mother through the birth canal and in mother’s milk. Since the infant immune system is immature, it allows these microbes to colonize the gut. As babies mature, the microbiota seem to help to establish higher level immune structures in the gut.

Creation of a “mucosal firewall” in the gut is part of the strategy to maintain stability. This firewall is made up of immune cells,  epithelial cells, antimicrobial peptides and IgA (an antibody secreted by mucus linings). It keeps the microbiota in and foreign microbes out.

epithelial cells, antimicrobial peptides and IgA (an antibody secreted by mucus linings). It keeps the microbiota in and foreign microbes out.

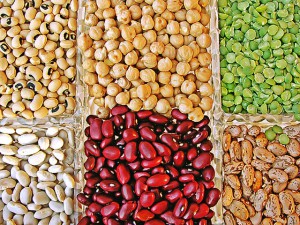

Humans rely on their microbiome to digest plant polysaccharides. Research has found that the amounts of fiber in the diet makes a difference in what inhabits the microbiome. A 2010 study compared microbes in the feces of 15 European children with 14 children from an African agricultural community. Researchers found a significant difference in the amount of Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes between the two groups—the African children had more Bacteroidetes than the European children. Additionally, the African children had two microbes the European children did not have. These microbes could digest cellulose and xylan. Moreover, the African children had significantly more short-chained fatty acids (SCFAs) than the European children. More on SCFAs later in the post.

In another study, researchers evaluated the microbiota of 76 infants at 3 weeks and 3 months of age. Then at 1 year, they administered a skin prick test to assess allergic reaction. Twenty-two of the infants showed a reaction to the skin prick. When the microbiota of those 22 were compared with those that did not have an allergic reaction, there was a significant difference in the ratios of microbiota in those who developed allergic reactions and those who didn’t. It appears that, early on, the composition of the microorganisms in the gut are determining how our immune system responds.

Short-Chained Fatty Acids

Another piece of the puzzle are the short-chained fatty acids or SCFAs that gut microorganisms produce. SCFAs like acetate, propionate, and butyrate are important products of fermentation of fiber in the gut and it’s the Bacteroidetes that produce SCFAs. Never heard of these fatty acids? Well, they are incredibly important to the immune system. In fact, the amount of SCFAs circulating in the blood and located in the colon seems to affect the regulation of the immune system.

Another piece of the puzzle are the short-chained fatty acids or SCFAs that gut microorganisms produce. SCFAs like acetate, propionate, and butyrate are important products of fermentation of fiber in the gut and it’s the Bacteroidetes that produce SCFAs. Never heard of these fatty acids? Well, they are incredibly important to the immune system. In fact, the amount of SCFAs circulating in the blood and located in the colon seems to affect the regulation of the immune system.

SCFAs are the main energy source for the epithelial cells that line the colon. SCFAs are important components of the pathways for tumor suppression and in anti-inflammatory pathways. SCFAs are also involved in regulating the immune systems responses, especially resolving inflammation. Even the size of the regulatory T-cell network in the colon is adjusted by pathways involving SCFAs. (For more information including videos on Pathways see Oncology Basics: Genes and Cancer Treatment. For further information on the immune system see Oncology Basics: The Immune System and Immunotherapy.)

So, it might be said that having the right combination of Bacteroidetes in your gut could help prevent many chronic conditions.

Nutrition and Obesity

An interesting study from 2009 utilized mice who were “germ-free” and so didn’t have a gut microbiome. In the study, these mice  received a human fecal transplant and thereafter produced the microbiome of the human transplant. First, they were fed a low-fat, plant-rich diet. Then, they were switched to a high-fat, high sugar diet. Only after one day of being switched to the “Western” diet, the structure of their microbiota changed. And that changed the metabolic pathways and gene expression of the microbiome as well. Furthermore, the mice changed physically, becoming fatter.

received a human fecal transplant and thereafter produced the microbiome of the human transplant. First, they were fed a low-fat, plant-rich diet. Then, they were switched to a high-fat, high sugar diet. Only after one day of being switched to the “Western” diet, the structure of their microbiota changed. And that changed the metabolic pathways and gene expression of the microbiome as well. Furthermore, the mice changed physically, becoming fatter.

This trait of increased “adiposity” (increased fat) was transferrable to other germ-free mice through fecal transplant. But what was also important was that a change back to the low-fat, plant-rich diet changed the mice microbiomes again. The fat mice could change back to “skinny” mice.

Making Connections

Are we beginning to unravel the intricate lacework of interactions between our symbiotes and ourselves? Could there be new therapies in the offing? Perhaps.

2016 study compared the microbial biodiversity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis with controls. The study found that people with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) had less diversity and that reduced diversity could be correlated with the amount of time the person had lived with RA and the amount of autoantibodies that the patients had. Additionally, those with RA had a larger number of rarer microbes than the controls. These rare lineages caused an imbalance in the flora of those with RA.

2016 study compared the microbial biodiversity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis with controls. The study found that people with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) had less diversity and that reduced diversity could be correlated with the amount of time the person had lived with RA and the amount of autoantibodies that the patients had. Additionally, those with RA had a larger number of rarer microbes than the controls. These rare lineages caused an imbalance in the flora of those with RA.

Patients with RA also had Collinsella present in their gut. In a follow-up in-vitro study, the researchers grew colon tissue in petri dishes. The exposed one set to E.Coli (control) and the other to Collinsella. After three weeks they compare the tissues. The tissues exposed to the Collinsella had a reduction in the proteins (called tight junction proteins) that held the cells together. The Collinsella exposed tissues became leaky. There was also an increase in the products of inflammatory pathways (interleukin and chemokines) in those Collisella exposed tissues.

This particular research is being conducted at the Microbiome Program at Center for Individualized Medicine at the Mayo Clinic. But there are more studies going on around the country.

The aphorism, “You are what you eat” seems truer than ever before. Eating a high fiber diet is good for your immune system and your overall health.

*archaea are bacteria-like organisms most of which can live in the absence of oxygen

**eukaryotes are single celled organism that have their DNA in a nucleus