As she sat on the paper-lined treatment table, surgery staples in a bag beside her, Caroline Wright learned her brain tumor was the deadliest type — a glioblastoma (GBM). [1] The average length of survival for this tumor is 8 months. [2] At the breakfast table one day, Henry, age 5, asked his mom, “Who will take care of me if you die?”

Caroline, an author, created several children’s books to help answer that question for her son and other families facing that question. People call her lucky because she is one of the only 6.9% of patients who has survived 5-years after GBM diagnosis. [2]

But luck should not define survival. Changing GBM and other deadly cancers’ trajectory for patients drives the work of many researchers. Recently, one team obtained crucial insights into how out-of-control cancer cells work, paving the way to more targeted treatments. [3]

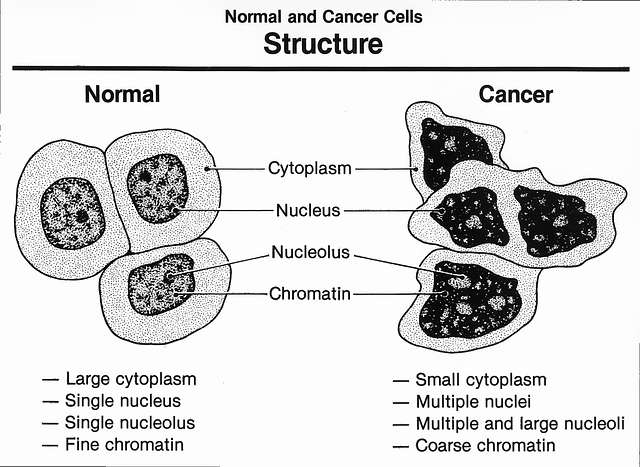

Inside cancer cells

Compared to normal cells, cancer cell nuclei are bizarrely shaped and sized.

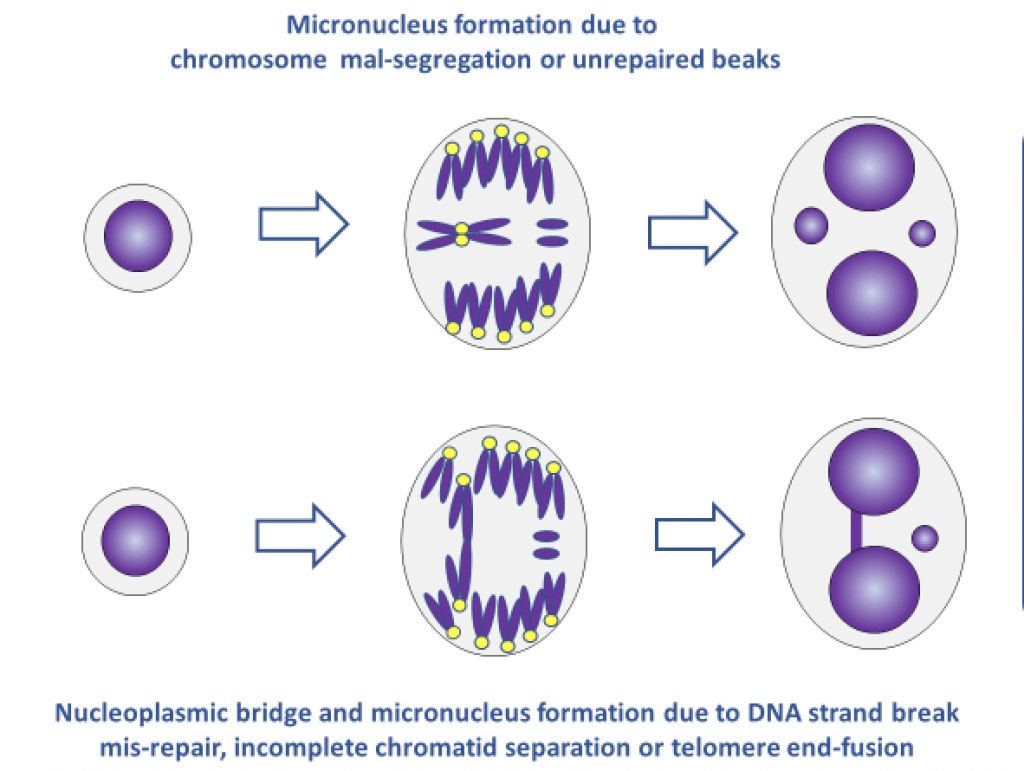

Nuclear envelopes surround the DNA of the primary nucleus and also multiple tiny nuclei (micronuclei).

The envelopes surrounding these micronuclei are fragile.

Chromosomal bridges (chromosomes that link two cells together) can also be present.

figure/fig2/AS:983878474928153@1611586316797/Formation-of-micronuclei-and-nucleoplasmic-bridges-in-cytokinesis-blocked-cells-For-the.ppm

Below are some examples of the images that these researchers were able to capture and share in their article. These are chromosomal bridges.

[from Supplements 7 and 8 of 2D and 3D multiplexed subcellular profiling of nuclear instability in human cancer. bioRxiv [Preprint]. 2023 Nov 11:2023.11.07.566063. doi: 10.1101/2023.11.07.566063. PMID: 37986801; PMCID: PMC10659270.]]

Micronuclei and micronuclei ruptures

Micronuclei may be important to malignancy and metastasis. Some get reincorporated into the primary nuclei, maintaining DNA damage acquired while in the micronucleus. Some are ejected from the cell, joining the crosstalk between cancer cells and their tumor microenvironment. Or nuclei envelopes rupture exposing chromosomal material to the cell’s cytoplasm. The DNA is cut up into fragments and randomly linked in the cytoplasm. These ruptures are common in GBM. [4]

[from Supplements 7 and 8 of 2D and 3D multiplexed subcellular profiling of nuclear instability in human cancer. bioRxiv [Preprint]. 2023 Nov 11:2023.11.07.566063. doi: 10.1101/2023.11.07.566063. PMID: 37986801; PMCID: PMC10659270.]

Using new technology including highly-multiplexed 2D and super-resolution 3D-imaging, the researchers showed just how common nuclei ruptures are in GBM: 10-25% of cells have primary nuclei ruptures and 1-10% of cells have micronuclei ruptures. They deconstructed these ruptures, recording the tiny structures and localized protein accumulations in the many-celled environment of tumors. In this way, they linked low levels of structural proteins in the envelopes (lamin A/C and lamin B1) to the ruptures. When primary nuclei ruptured, those envelopes had reduced lamin A/C protein. When micronuclei ruptured, they contained low levels of lamin B1. Researchers also saw issues with nucleus membrane repair mechanics in the GBM cells. [3]

Their new technology made it possible to understand the spatial organization of GBM tumors. GBMs include at least four types of cells. The team linked spatial location with lamin expression and rupture frequency, finding that primary and micronuclear envelope ruptures are most common in neural-like progenitor (NPC-like) cells. Micronuclei ruptures amplified oncogenes and caused catastrophic chromosomal shattering and rearrangement (chromothripsis). NPC-like cells were found at the edges of the tumor, right next to normal, healthy cells, perhaps indicating that rupturing micronuclei drive tumor progression. [3] (In the video below, note the NPC-like cells are on the outer side of the tumor.)

[from Supplements 7 and 8 of 2D and 3D multiplexed subcellular profiling of nuclear instability in human cancer. bioRxiv [Preprint]. 2023 Nov 11:2023.11.07.566063. doi: 10.1101/2023.11.07.566063. PMID: 37986801; PMCID: PMC10659270.]

The team also detected chronic inflammation in the tumor. DNA left outside the nucleus after normal cell division shows that either cell damage or an infection has occurred. Normally, a process called the cGAS/STING pathway starts producing interferon, an inflammatory substance that activates the immune system, triggering an immune cell (like a macrophage) to eat the sick cell.

In the cancer environment, the chronic inflammation observed in GBM seems to rewire the cGAS/STING pathway, changing the microenvironment to support the tumor instead of killing the defective cells. Chronic inflammation may also support epithelia-mesenchymal transition where cells lose adherence to each other, making them mobile and starting the process of metastasis. [3]

The researchers recorded the characteristics of GBM cancer cell nuclei, especially the instability of their membranes and the impact of immune system responses to cancer. Crucially, their work supports and explains previous research. Additionally, their research identifies and visualizes therapeutic opportunities, specifically targeting disruptions in nuclear envelope repair mechanisms, as well as low-level proteins in the nuclear envelopes, immune pathways and more. [3]

To see visualizations of the processes in the research revealed, follow the links to videos in the published findings. [Supplements 7 and 8].

New therapies are desperately needed for the deadliest of cancers. Seeing what happens in the environment of the tumor can make a world of difference.

Making a Difference

Caroline answered Henry’s question about who would care for him by saying, “The same people if I live.” Listing relatives and close friends she told him, “Your life will be filled with love, mine and others, whether it comes from my body or not.” She wrote a book called Lasting Love for children who lose a loved one.

Her doctor uses the word “miracle” to describe her survival. [1] Yet, waiting for miracles is not enough. Driven to change the experiences of the other 93% of patients diagnosed with GBM, researchers are conducting cutting-edge research to find targeted treatment.

References:

[1] Wright C. After I Was Given a Year to Live, I Wrote This Book for My Sons and Fought Brain Cancer with Love. People. 2019 Aug 20. https://people.com/human-interest/author-caroline-wright-brain-cancer-book-for-sons/

[2] About Glioblastoma. National Brain Tumor Society. 2024. https://braintumor.org/events/glioblastoma-awareness-day/about-glioblastoma/

[3] Coy S, Cheng B, Lee JS, Rashid R, Browning L, Xu Y, Chakrabarty SS, Yapp C, Chan S, Tefft JB, Scott E, Spektor A, Ligon KL, Baker GJ, Pellman D, Sorger PK, Santagata S. 2D and 3D multiplexed subcellular profiling of nuclear instability in human cancer. bioRxiv [Preprint]. 2023 Nov 11:2023.11.07.566063. doi: 10.1101/2023.11.07.566063. PMID: 37986801; PMCID: PMC10659270.

[4] Di Bona M, Bakhoum SF. Micronuclei and Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2024 Feb 8;14(2):214-226. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-23-1073. PMID: 38197599; PMCID: PMC11265298.