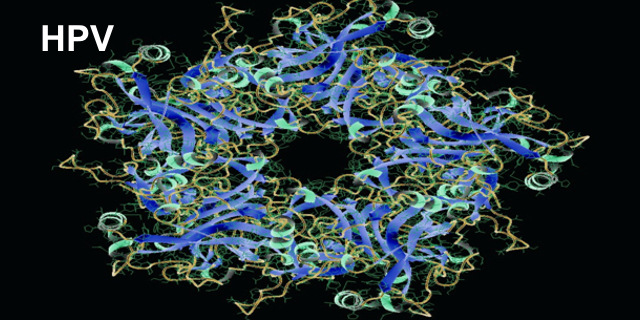

It’s been less than 40 years since the Human Papillomavirus (HPV) was discovered and isolated.1 Since then, more than 100 types or variants have been found. Most of them are symptom-free, but several variants are associated with cervical cancer.

HPV-16 and HPV-18 are the first two variants discovered that are associated with cancer; HPV-16 is in 50 percent and HPV-18 in 20 percent of cervical cancer biopsies, respectively.1

Low levels of awareness of HPV’s prevalence and limited recognition of the ways it is spread challenge prevention efforts but also cause problems with stigma and victim-blaming. Although HPV is the most common sexually transmitted infection, there is also strong evidence of non-sexual HPV transmission. Vertical transmission from mother to baby is possible.2 Moreover, HPV is highly resistant to disinfectants. The DNA from HPV has been found on reusable ultrasound probes used for trans-vaginal, trans-rectal, and trans-esophageal ultrasound medical procedures.3

These facts, plus the huge numbers of people in the US who have or have had HPV – between 75 to 80 percent of people age 15 to 49 in the US have had HPV4 – makes one wonder that cancers associated with HPV do not occur at even higher rates. Several cancers are caused by HPV. Cervical cancer is just one of them. More than 13,000 women are diagnosed with cervical cancer in the United States each year.5 Around 70% of oropharyngeal cancers -cancers of the back of the throat, base of the tongue and tonsils – as well as cancers of the vulva, vagina, penis and anus are caused by HPV.6

Stigma

The discovery of HPV variants that cause cancer has become an added burden to women who have been diagnosed with cervical cancer – they face the assumption that they have brought their cancer on themselves as a sexually-transmitted disease. A qualitative study conducted in England included one-on-one interviews and a focus group with women who had just received positive HPV results with abnormal pap smears and women who had not. Researchers found that the women in long-term relationships who were HPV positive had trouble coming to terms with the diagnosis. Articulating shock and embarrassment, they tried to figure out how they could have been infected. They didn’t understand that their partners’ status could impact their health.7

In another study in 2010 using quantitative survey and in-depth interviews to learn how an abnormal Pap smear and HPV positive diagnosis impacted patients, researchers found patients experienced self-blame, fear, stigma, feelings of powerlessness and anger.8 In yet another study, done in 2013, compared the stigma felt by women infected with HPV with men infected by HPV and found greater association of negative emotions and stigma among women than among men.9

Spread the Word

In 2006 an HPV vaccine was approved for girls and young women; in 2010 the vaccine was approved for boys and young men.10 In October 2018, the FDA expanded the age of HPV vaccinations to 45 years for both women and men.11 Perhaps the stigma that women have experienced will begin to diminish as the truth about this pervasive virus is shared and more people are vaccinated. In the meantime, share the information about the many ways that HPV is spread and the numbers of people who have been or are carrying HPV. Getting this information out may reduce the stigma that women and men feel when they get these cancers. Cancer is hard enough without any extra burdens.

References

1 https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/2008/hausen/biographical/

2Lee, S. Park,J. Norwitz, E. et al. (2013) Risk of Vertical Transmission of Human Papillomavirus throughout Pregnancy: A Prospective Study. PLoS One. 8(6): e66368.doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066368

3Ryndock, E. & Meyers, C. (2014) A risk for non-sexual transmission of human papillomavirus?, Expert Review of Anti-infective Therapy, 12:10, 1165-1170, DOI: 10.1586/14787210.2014.959497

4https://www.plannedparenthood.org/learn/stds-hiv-safer-sex/hpv

5https://www.nccc-online.org

6https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/basic_info/hpv_oropharyngeal.htm

7 Patel, H. Moss, E., Sherman, S. (2018). HPV primary cervical screening in England: Women’s awareness and attitiudes. Psycho-Oncology 27(6): 1559-1565.

8Daley, E. Perrin, K. McDermott, J. (2010). The psychosocial burden of HPV: a mixed-method study of knowledge, attitudes and behaviors among HPV+ women. Journal of Health Psychology, 15(2):279-90. Doi: 10.1177/1359105309351249.

99 Daley, E. Vamos, C. Wheldon, C. (2015). Negative emotions and stigma associated with a human papillomavirus test result: A comparison between human papillomavirus–positive men and women, Journal of Health Psychology, 20(8), 1073–1082. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1359105313507963

10Chaturvedi, A. Graubard, B. Broutian, T., (2018) Effect of Prophylactic Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccination on Oral HPV Infections Among Young Adults in the United States J Clin Oncol. 36(3): 262–267.doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.75.0141

11https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-expanded-use-gardasil-9-include-individuals-27-through-45-years-old

What about the dangers of reusing medical equipment for let’s say a colonoscopy? What are the risk/benefits here? Disinfectant can’t fully disinfect. Surely disposable units can be put into use with HPV risk to patients.

I have being suffering from Parkinson disease for 4 years now at 47 yearsof age till i used Madida herbal medicine. I used to have sleepless night, tremors, weakness, slow movement etc. I was placed on Sinemet for 7 months and then Sifrol and Rotigotine was introduced which replaced the Sinemet but I had to stop due to side effects. Last year, I started on Parkinsons disease herbal treatment from Madida Herbal Clinic, this natural herbal treatment totally reversed my Parkinsons disease. Visit: www.madidaherbalclinic.weebly.com, email madidaherbalcenter@gmail.com for more information. The treatment worked incredibly for my Parkinsons disease, i have a total decline in symptoms including tremors, stiffness, slow movement and others.