Thirty-eight states in the US have passed “Right To Try” laws. These are laws that are created to give terminally ill patients who have run out of options access to experimental drugs that have not completed the FDA approval process. There is an effort underway to pass this type of legislation on a federal level.

On February 8, the #LCSM (Lung cancer social media) twitter chat “took on” the debate over “Right To Try.” Dr. Jack West presented questions; patients, caregivers, physicians, researchers and advocacy group representatives discussed the pros and cons. The first answers to his question immediately illustrated the divide.

T1) Do we really need a nat’l “Right to Try” legislation, beyond today’s Expanded Use/Compassionate Use for investigational agents? #lcsm

— H. Jack West, MD (@JackWestMD) February 9, 2018

A1: No, in fact it could reduce or threaten the protections afforded to patient through the current process #lcsm

— LUNGevity Foundation (@LUNGevity) February 9, 2018

But patients and caregivers are desperate for access.

A1: only needed if it will help patients get these drugs more quickly. Seems to take forever to get drugs via compassionate use. #LCSM

— Leslie Trahan (@lestrahan) February 9, 2018

I would give everything I own plus some if it could save/prolong Andy’s life. #lcsm

— Leslie Trahan (@lestrahan) February 9, 2018

This is an emotional issue. It sounds like a good idea–give people who are desperate for experimental drugs access to them and reduce the liability of pharmaceutical industry if they provide the drugs–but is it?

To make a decision, it’s important to have some background and understanding. Here’s some history to get started.

When the FDA approval process got teeth

Establishing safety and effectiveness

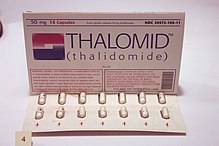

After World War II, a lot of people in Europe and the US were having trouble sleeping at night. Invented by the German cosmetic firm, Chemie-Grünenthal GmbH, thalidomide entered the market as an over-the-counter drug in 1956. Marketed as the only non-barbiturate sleeping aid around, it was a hit. But a side effect, peripheral neuropathy, caused the German regulators to make it a “prescription only” medication. As sales slumped, the producer looked for other ways to market their product. They found a distributor and marketed thalidomide as a morning sickness pill in Germany and overseas. In late 1960, Dr. William McBride, an Australian obstetrician, started prescribing it for patients experiencing severe morning sickness. Nine months after the fact, his patients delivered babies with severe deformities: missing or short limbs, missing ears and eyes, and internal organs. He compiled his findings and exposed thalidomide’s “side effects” in a letter to the editors Lancet, published in December 1961.

effect, peripheral neuropathy, caused the German regulators to make it a “prescription only” medication. As sales slumped, the producer looked for other ways to market their product. They found a distributor and marketed thalidomide as a morning sickness pill in Germany and overseas. In late 1960, Dr. William McBride, an Australian obstetrician, started prescribing it for patients experiencing severe morning sickness. Nine months after the fact, his patients delivered babies with severe deformities: missing or short limbs, missing ears and eyes, and internal organs. He compiled his findings and exposed thalidomide’s “side effects” in a letter to the editors Lancet, published in December 1961.

Meanwhile, the manufacturer was actively pressing the FDA to approve their medication for distribution in the US. Frances Kelsey, an FDA inspector, held up the approval because she felt that the evidence provided by the company was inadequate. Her efforts were rewarded with recognition by President Kennedy and with the passage of a new law in 1962 which tightened the approval process for medications–requiring proof of safety and effectiveness.

After the law’s passage, the FDA reviewed thousands of drugs that were on the market. They found that 70% of the drugs were making claims that weren’t supported by evidence.

So the approval process, going through Phase 1, 2 and 3 clinical trials are to determine safety (Phase 1) then effectiveness (Phases 2 & 3). Of 100 possible drugs that enter Phase 1, only 5 make it through.

Compassionate Use

Next question: Is there a process in place now for terminally ill patients to have access to experimental drugs if they have run out of options?

Yes. During the AIDs epidemic in the late 1980s and 90s, activists pushed for reforms of the FDA process. A program called “Compassionate Use” was started in 1987. Then in 1992, an accelerated approval process was implemented through Congressional action to let FDA approve drugs for life threatening diseases before the drugs were demonstrated to extend patients’ lives.

Finally, Compassionate Use was expanded in 2009 to get patients access to experimental treatments when they could not enroll in clinical trials.

How it works

Compassionate Use is also called Expanded Access. According to the FDA, completion of a form, called an Emergency Investigational New Drug (EIND) Application takes around 45 minutes –changed in 2014 from a 100 hour process-and is submitted by the patient’s physician. . These emergency requests have a turn-around time of 24 hours. Approval rates are at 99%. However, a fact that influences this approval rate is pharmaceutical company agreement to provide the treatment.

One benefit of FDA review of these requests is that the FDA scientists have access to confidential information provided by the pharmaceutical agency, that the patient’s doctor doesn’t have. With that information, the FDA can make safety-oriented changes, like adjusting the dosage or the frequency of the treatment. This protects the patient from the very beginning.

Supporters of “Right To Try”

I was told I would die in a year. Used med every oncologist knew worked but was technically off labei. Am here 9 yesrs later. Would I I have taken a risky Phase I drug ar that time weighing possibility versus certain death? Yes. #lcsm

— Bob Tufts (@TuftsB) February 9, 2018

I’m sure patient groups will find that risks might outway, but I’m wondering how many actual pts would say no to something if last possible treatment option. My husband was asking about a liver transplant. He would’ve done anything to live. #lcsm https://t.co/eO1VVHuaNI

— Kristine Cherol (@kscoon) February 9, 2018

People who support “Right To Try” feel that desperately ill people should be able to choose for themselves if they want to take a risk with investigational drug. Additionally, supporters would like this legislation to force drug makers to provide experimental medications to dying patients. And there are some who believe that “Right To Try” will reduce the waiting time for experimental treatments as compared to the FDA’s Compassionate Use.

Critics of “Right To Try”

Those who oppose “Right To Try” legislation have many concerns. First, they say that “Right To Try” legislation should be renamed “Right To Ask” because these laws don’t require pharmaceutical companies to supply the treatments.

Another negative they cite is that neither physicians nor the pharmaceutical industry are held liable should something go wrong with the treatment.

Those who oppose are concerned that patients will want to opt out of treatment that is standard of care (SOC).

T1: Might it cause more patients to ignore SOC treatments in favor of untried or unsafe methods touted through the grapevine? #lcsm

— Karen Loss (@cancertrek) February 9, 2018

Moreover, legislation that has been passed in the states allow insurance companies to drop coverage of patients who use “Right To Try” treatments. Additionally, patients can become ineligible for hospice care. Health insurance doesn’t have to cover any complications that arise with the experimental treatment and the law in Colorado allows insurance companies to deny coverage for as long as 6 months after receiving the last treatment of an experimental drug.

“Right To Try” opponents are concerned that participation in clinical trials will suffer if patients are able to obtain experimental medication outside of clinical trials. Not only that, if a patient receives “Right To Try” treatment and is injured by that treatment, the FDA cannot use this information to deny drug approval.

Gut An Established Program or Improve It?

As a patient with metastatic cancer wrote in an opinion of post for Slate:

“For nearly a decade, the FDA’s expanded access program has been available for people like me who are fighting life-threatening diseases and who want the option to have access to new therapeutic approaches in a responsible and ethical manner, especially when there is no other FDA-approved treatment option. And that means we already have a right to try, one that offers greater protection for the already vulnerable individuals.”

The FDA’s Compassionate Use/Expanded Access program needs further work.

A1- it’s my understanding- at least from secondhand experience that sometimes Compassionate Use can be a bit difficult. I’m for it if “right to try” makes it easier for access. #LCSM https://t.co/ntDB6ZIJst

— Kristine Cherol (@kscoon) February 9, 2018

First, there are still issues around the timeframe and difficulty of getting access through Compassionate Use.

T1 Right to try laws in the states haven’t made much difference in patient access that I can see. Laws don’t force pharma to make their drugs available for free to anyone who wants them. They just make docs less liable. #lcsm

— Janet Freeman-Daily (@JFreemanDaily) February 9, 2018

Second, requiring the pharmaceutical industry to supply the treatment would improve the process.

In an almost perfect world, FDA compassionate use would 1)require pharma to supply drug, 2) be less cumbersome (private practice oncs don’t have IRBs), 3) would allow us access earlier, before on death’s doorstep. Since world is far from perfect, RTT is an imperfect option #LCSM

— Dr. Kelly Shanahan (@stage4kelly) February 9, 2018

Third, as this patient (and retired ob-gyn) with metastatic breast cancer states–Compassion Use needs to allow earlier access.

Fourth, clinical trial eligibility requirements need to be fixed.

Very true. Would add that many patients in clinical trials are afraid/hesitate to report side effects for fear of being removed from the trial. #lcsm

— Enlightening Results (@GraceCordovano) February 9, 2018

Real important issue. ASCO looking at this. Lots of silly eligibility criteria will get amended hopefully. #lcsm

— Dr Riyaz Shah (@DrRiyazShah) February 9, 2018

Need to eliminate ritual exclusions. MT @DrRiyazShah: @cancertrek important. ASCO looking at this re: silly eligibility criteria. #lcsm

— H. Jack West, MD (@JackWestMD) February 9, 2018

Kelly from metastatic breast cancer land here. In a perfect world all advanced/metastatic cancer patients would be in clinical trials (in their hometowns) and this would be moot. #LCSM

— Dr. Kelly Shanahan (@stage4kelly) February 9, 2018

The Bottom Line

The “Right To Try” state-level legislation have stripped protections from extremely vulnerable people. Perhaps, instead of reducing the FDA’s mandate, implementing changes to Compassionate Use would improve access and provide patients hope.

What do you think? Please share your thoughts about this issue in the comments section.

One problem is that even “right to try” does not make medications available which (typically for patent reasons) pharma does not pursue simply because they are uneconomic in the face of the billion dollars required to get regulatory approval.

Two good examples: Tempol as an anticancer agent is being investigated at both the NCI and the FDA itself. Per FDA and NCI researchers, a derivative (mito-tempol) works about as well as doxorubicin in an animal model for breast cancer, while at the same time cutting the toxicity of doxorubicin.

Both actions of such SOD’s and SOD-mimetics have been known since the 1970’s, without a single product approval. Such agents have little toxicity. So this is for economic reasons.

The other example is the use of Inosine to slow the evolution of Parkinsons by raising levels of the endogenous antioxidant and neuroprotectant uric acid. This is currently in Phase-3 trials sponsored by the Michael J Fox Foundation.

Other studies involve ALS. Urate infusion is even being used to treat acute ischaemic stroke. As with Tempol, inosine is “off the shelf”. So no drug company will touch it.