“Have patience with everything that remains unsolved in your heart.

…live in the question.” —Rainer Maria Rilke, Letters to a Young Poet

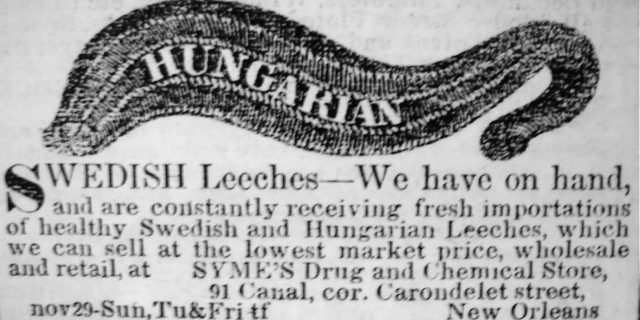

Leeching or blood letting was part of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century. Instead of a lancet, leeches were placed on various parts of the body to slowly remove blood. Leech farms, called leecheries, were all the rage, a way to mass-produce medicinal leeches as opposed to horse leeches. Long debates over the use of wild leeches versus these leecherie leeches were part of the medical literature of the time.

Why this look at medicine’s past?

Dealing with the uncertainty of not knowing what caused disease made for many useless and dangerous practices in medicine. “Not until early in the twentieth century did a sick person have a better-than-even chance of benefiting from consulting a physician,” says Katherine Montgomery, MD, author of How Doctor’s Think.

Medicine Today

Today, we believe that medicine is a science. And yet, as Dr. Nicholas Capozzoli of Annapolis, Maryland states in a post on The Healthcare Blog, “In my neurology practice, I often can’t make a specific diagnosis even after taking a careful history, doing a thorough physical exam, and ordering all the appropriate diagnostic tests. Such uncertainty is inherent in most of medicine — it is sad but true that lots of problems elude our current medical tools and knowledge.”

Quotes about Uncertainty

So is medicine a science? Is it an art and a science? Dr. Montgomery believes, “We make a great, even dangerous mistake about medicine when we assume it is a science in the realist Newtonian sense we learned in high school…assuming that medicine is a science leads to the expectation that physicians’ knowledge is invariant, objective, and always replicable…”

Becoming a physician is all based on learning disease stories. Students chart descriptions of a patient’s history, starting from the very beginning and creating narratives that are acceptable to their teachers. Their teachers try to mold them into detail-oriented knowledge seekers dedicated to providing the best for their patients.

But in the end, “clinical knowing remains first of all the interpretation of what is happening with a particular patient and how it fits the available explanations. Such knowledge is still called an opinion,” says Dr. Montgomery.

In other words it is uncertain. Albert Einstein stated that, “As far as the laws of mathematics refer to reality, they are not certain; and as far as they are certain, they do not refer to reality.” Richard Feynman agreed and took his view of uncertainty even further, “I think it’s much more interesting to live not knowing than to have answers which might be wrong…I am not absolutely sure of anything.”

Dr. Capozzoli embraces the uncertainty of his profession. “I’ve become quite comfortable saying that I simply don’t know what’s causing the problem. It serves my patients well to admit that things are still too unclear to call….as physicians, I believe we should carefully guard against hubris. True expertise lies in being comfortable with our limited knowledge, not denying it.”

One of the funniest comedians died of ovarian cancer, but before she died Gilda Radnor left us with something more than laughter. She said, “I wanted a perfect ending. Now I’ve learned, the hard way, that some poems don’t rhyme, and some stories don’t have a clear beginning, middle, and end. Life is about not knowing, having to change, taking the moment and making the best of it, without knowing what’s going to happen next. Delicious Ambiguity.”

How do you feel about the uncertainty of medicine? Do you feel comfortable with your physician saying, “I don’t know”? Do we expect too much of physicians?

The very BEST physicians are those who are able to say, “I don’t know.” They are willing to share what they do know. They can speak to us in ways that allow us to understand the value of any given treatment and the possible downside so we can make informed decisions. Shared decision making is important to me as both a patient and an advocate for others. Time to personalize the conversation, to tailor the information to what is happening in MY body at any given time is paramount. That requires communication that is two sided.

I love this piece. I’m going to read the book you cite and I’m going to reread another book, also titled “How Doctors Think” that was written by Jerome Groopman. I read it when it was first published in 2007 and I already pulled it off the shelf.

I would much prefer that a doctor tells me they aren’t sure or don’t know. I am mature and intelligent enough to accept that no one can possibly have all the answers. I aim to cultivate a very healthy disrespect for all professionals on the basis of this fact.

Thank you so much for commenting. I completely agree that it’s important to have clear communication between patient and physician.