Any Trekkie (Star Trek Fan) would know this greeting of the Borg that ends with “Resistance Is Futile.”

What Does Compliance Mean?

According to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, compliance is “the act or process of doing what you have been asked or ordered to do.”

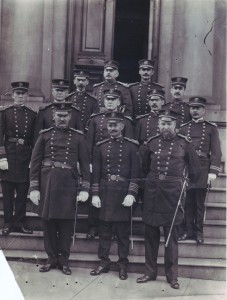

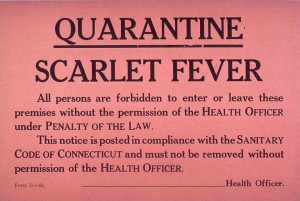

This word is part of the legal, militaristic language of quarantine. In the US, Congress enacted legislation in 1878, 1890, 1893, and 1906 that established the Public Health Service to “prevent introduction of epidemic diseases” into the US and “prevent the interstate spread of communicable diseases.” The Public Health Service was organized in 1889 along military lines with commissioned officers.

This word is part of the legal, militaristic language of quarantine. In the US, Congress enacted legislation in 1878, 1890, 1893, and 1906 that established the Public Health Service to “prevent introduction of epidemic diseases” into the US and “prevent the interstate spread of communicable diseases.” The Public Health Service was organized in 1889 along military lines with commissioned officers.

Perhaps the birth of the pejorative terminology of “compliance” comes from the efforts to control outbreaks of diseases like tuberculosis. People who did not comply were termed “ignorant, vicious, recalcitrant, or defaulters.” Even research on medication taking conducted before 1960 describes people who didn’t take their medicines as prescribed as “untrustworthy.”

From Compliance To Adherence

The language of medication taking has moved away from “compliance” to “adherence” but many would say this is not much of a change.

What does adherence mean? Adherence is “the act of doing what is required by a rule, belief, etc.” One article written in 1999 suggested that, while “The term “compliance” suggests a restricted medical-centered model of behavior…the alternative, “adherence” implies that patients have more autonomy in defining and following their medical treatments.”

etc.” One article written in 1999 suggested that, while “The term “compliance” suggests a restricted medical-centered model of behavior…the alternative, “adherence” implies that patients have more autonomy in defining and following their medical treatments.”

When studying medication taking, these words create problems. For example, these words imply a dichotomy: either you are adherent or you are non-adherent. What if you forget to take your medication once or twice, but otherwise stay on track with the treatment? You would be classified as non-adherent. What if you take your medication consistently but it is at a lower dose? You are adherent: but there are different behaviors going on beyond yes, you take your medicines and no, you don’t.

Furthermore, these words stigmatize people who may not have taken every pill at the desired time and, in turn, can interfere with relationships between those people and future providers.

How Do People With Chronic Conditions Feel About These Words?

During a tweetchat held in March 2015, a variety of people with chronic conditions (and their caregivers) shared their feelings about the words “Compliance” and “Adherence.” Their conditions varied from gastroparesis and diabetes to migraine, stroke and chronic pain. There is more from this discussion in the follow up post.

“Adherence” and “compliance” both seem like orders — like the patient is too uninvolved in the decisions. #hchlitss

— Melissa VanHouten (@melissarvh) March 27, 2015

T1 HATE hate hate hate the word “adherence.” Makes pts who cannot follow instructions to the letter seem like unruly children. #hchlitss

— Laurel Ann Whitlock (@twirlandswirl) March 27, 2015

These patients have strong negative feelings about the words of medication taking that are part of the lexicon of the pharmaceutical industry, medicine and the healthcare system.

Every patient wants to be well. When we use words like “compliance” it implies HCPs and patients somehow have different agendas. #hchlitss

— Jennifer Celio (@JMCelio) March 27, 2015

T1 – “obedience” comes up as synonymous with both adherence and compliance #hchlitss

— Patti Koblewski (@ChronicPainGPS) March 27, 2015

What is it we’re trying to say when we say “compliant?” If it’s that they’re taking their meds, then why not just say that? #hchlitss

— Jennifer Celio (@JMCelio) March 27, 2015

Rethinking “Compliance” and “Adherence”

Should the language of medication taking change? What are reasons behind not taking medication as prescribed? This is the first post on this important topic. Please feel free to join the conversation (in the comments section) as we explore medication taking.

Tweets from the HCHLITSS Tweetchat March 27, 2015.

why not just say medication taking? It is naming the behavior without judgement.

Two related terms I also like our concordance and shared decision-making. These terms refer to the conversation between the individual and their health care provider. Both of these are models stress the importance of sharing power. Still these terms refer to the process not the behaviour of taking medications. Thanks for kicking off a conversation on this important topic.

One of my favourite topics, Kathleen. Although both “compliance” and “adherence” (slightly less patronizing) are cringe-worthy terms, I’m afraid I haven’t yet come up with a less loaded word.

The reality is that when patients don’t take medications that are recommended for their diagnosis (for whatever reason), the results can often be catastrophic for the patient. It IS a serious problem. I’ve written about this issue a number of times, specifically on the need to figure out the reason we do not take our meds – instead of jumping to the conclusion (as the tech hypemeisters of Silicon Valley are wont to do) that all a naughty non-compliant patient needs is another flashing beeping digital pillbox or phone app…

We know that about 50% of patients with chronic conditions stop taking their prescribed medications, and one-third never fill their prescriptions in the first place. An often-overlooked stakeholder issue is this lost sales opportunity for the pharmaceutical industry – an estimated $30 billion in revenues per year. It’s why industry has become so involved in launching their own compliance programs. As in all things, follow the money…

In answer to your last question, read “Why Don’t Patients Take Their Meds As Prescribed?” – http://myheartsisters.org/2012/12/13/why-dont-patients-take-their-meds-as-prescribed/

regards,

C.

Two big issues in people not taking their medications are out-of-pocket cost and time constraints. With insurance, my pharmacy was about to charge me $300 for a month of *one* medication, which is my entire month’s family food budget. (My employer changed pharmacy benefit managers.) People on public assistance know there is a secondary market for their medications, and often must sell them in order to pay the rent, car payment, etc.

Time constraints come to mind when you are in a public-facing position where you are not allowed (or it is frowned upon, etc.) to take medications while on the clock. Americans With Disabilities Act is pretty much useless, because these businesses are so sparsely staffed that there is nobody to relieve you for the minute (or five, if you have to walk to a car or locker to get your medication) it takes to correctly consume the medication.

I hear doctors complain, like petulant children: ‘Why don’t patients do what I tell them?’ Ironically, I rarely hear docs themselves use those hateful words to express their frustration ‘Why aren’t my patients compliant? Why don’t my patients adhere?’ Another thing I rarely hear of: doctors digging deeper to determine why those naughty patients don’t do as their told. In addition to the common reasons (cost, side effects, drug interaction/medication burden, forgetting) another reason for not taking meds that’s rarely acknowledged – let alone properly addressed – is not interpreting meds admin instructions as intended. Even seemingly simple directions can confound: eg: ‘take one pill when you wake up’. For an elderly gent, who nods off several times during the day, ‘waking up’ also happens several times a day. Or the husband and wife who both took her birth control pills. Or the woman instructed to put on a meds patch every day – but was not instructed to take the old patch off. I hope that encouragement to to take more responsibility for our health one day fosters the confidence to say to the doctor – or, perhaps, more likely the pharmacist, “I need to make sure I understand how to take these meds properly and how to fit them into my day-to-day”. If a patient doesn’t understand what ‘three times a day’ means in practical terms, not only can this lead to (ugh) non-compliance, but the risk of serious medication error.

I created 10second MedSchool videos to illustrate,

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lJOYjpwtlBQ&list=PLFP44u_0PAFfXQeT3Mh7fX7RBZRJZlnuQ

If providers and patients practice shared decision making, then patients and providers BOTH play a role in successful treatment with medication, which demands follow-through from both parties. The patient needs to take the medication and report back to the provider regarding side-effects, the amount of symptom improvement, and any obstacles to sticking with the plan. The provider may need to respond with a change in dosage or medication type. The provider is also responsible for asking questions about the treatment during future conversations. So perhaps, “medication follow-through” is a term that includes the responsibilities both parties have to assure that treatment with medication is optimized.

I agree that both “compliance” and “adherence” leave much to be desired from a patient’s perspective. However, there are two elephants in this conversation that could complicate the issue. First, many individuals aren’t really aware of what specific factors prevent them from following their physician’a medical advice or actively engaging in their own treatment plan. For example, a patient may not take their medication as prescribed and report undesirable side effects as the reason. Yet, only one medication may have undesirable side effects while the rest of the treatment plan doesn’t “fit” into the patient’s life (whether the instructions are complicated and poorly explained, the plan is cost prohibitive, or any number of psychosocial factors). Secondly, HCPs are seeing more and more patients everyday. There is less time to develop that personal relationship necessary to openly and honestly communicate with the patient combined with less knowledge of the patient as an actual human that must live a complex life outside of their HCP’s office. I’m afraid that the situation will get worse before it gets better.

There must be change on all fronts: patients need to take ownership of their role in decision making while physicians must understand they are not the sun which patients revolve around. Physicians must recognize the complex nature of a patient’s life and work with that patient to meet health goals. If a patient is labeled as non-compliant the physician must acknowledge that they are failing in some way as well.

Thank you for your thoughtful insights. There is a follow-up post coming which will delve into the “elephants in the room.” I will cite your comments! Kathleen

Dr. Montori has an interesting tool to assist physicians in shared decision-making for diabetes meds. https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=NECp7TtEzM4

@KathyKastner I love your YouTube 10-Second Medical School Playlist!! Excellent videos – short, funny, and on-point advice for better communications with patients!

– @disparityreport

Kathleen – your blog post captures my feelings about these 2 words exactly. I’ve always felt that they were unnecessarily militaristic, patronizing, placing the blame on the patient, without considering factors that may be beyond the patient’s control.