Pain has been defined by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) as, “An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage.” [1] There is a long added note to this definition which acknowledges that “Pain is always subjective” and “that if someone regard[s] their experience as pain and if they report it in the same ways as pain caused by tissue damage, it should by accepted as pain.” [1]

Well, isn’t that good news!

If you sense a touch of sarcasm, it may be because being believed is one of the challenges people with chronic pain experience. In fact, people with Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS), a condition where measurable physical changes can be seen in the body, still have problems being believed by family, friends and medical professionals.

Even physicians have had this experience. A clinical immunologist, writing in 2012, described what it was like being diagnosed and treated for CRPS. First, there was a delay in diagnosis. She consulted five physicians, four that were associated with the university teaching hospital where she worked. No one diagnosed CRPS. Then she had a delay in obtaining expert treatment. Even those who claimed to be experts in treatment were behind on the literature. Her third barrier was getting treatment that would work. A final barrier was that physician experts lacked the knowledge of how symptoms spread—actually insisting that she was having panic attacks, instead of recognizing clear symptoms of the disorder. So this physician turned patient—with greater access to care and “supposed” competence—underwent an intense ordeal and experienced disbelief from her peers. [2] It’s little wonder that regular people have similar or worse experiences.

CRPS is Real

CRPS is a real condition, with measurable physical changes in the body. It’s not psychological or “all in your head.” writes Dr. Elan Schneider in his CRPS guidebook. [3] Dr. Schneider is a physical therapist and co-founder of an exciting new treatment in the form of an application/game called TrainPain.

Here are a list of physical symptoms of CRPS:

- Constant intense pain, burning, throbbing and swelling in the painful area

- Pain that changes in intensity, but often feels much worse than may be expected

- Sensitivity to cold or touch

- Joint stiffness, swelling

- Muscle weakness

- Decreased ability to move

- Loss of fine motor control

- Tremors or spasms

- Stiffness

- Spreading pain

- Shiny thin skin

- Skin that feels warmer or cooler than usual

- Increased sweating

- Skin that changes color—white blotchy, red, blue

- Dry and withered skin

- Brittle, thickened nails [2]

On his website, Dr. Schneider introduces CRPS with a YouTube interview with Chaplain Bonnie Lester. The importance of this interview as an introduction to CRPS should not be underestimated. Most articles and information suggests that long-term CRPS does not see improvement. [4] Yet, after learning about neuroplasticity, Ms. Lester, who had had CRPS for over 20 years, is now pain free.

How Does Pain Start and CRPS Begin?

There are special nerve cell endings that initiate the sensation of pain all around our body. These nerve cells are called nociceptors. There are two kinds of nociceptors: the first type are called A-delta fibers, the second are called C-fibers. A-delta fibers are small, myelinated (covered with myelin) nerves that produce sharp, well-localized pain while C-fibers produce slow, poorly-localized pain—the burning, throbbing pain that many experience.

When we get a cut, the cells that are damaged release chemicals that stimulate the nociceptors and the immune system. An inflammatory response begins, where immune cells and extra fluids are called to the injury. Additionally, the nociceptors propagate the information that an injury has occurred to the spinal cord.

The spinal cord is like a relay station where the information about pain, temperature, and pressure from the skin, joints, and muscles can travel up to the brain. At the spinal cord, the nociceptors release pain neurotransmitters to a second neuron, which crosses to the opposite side of the spinal cord from where the injury occurred.

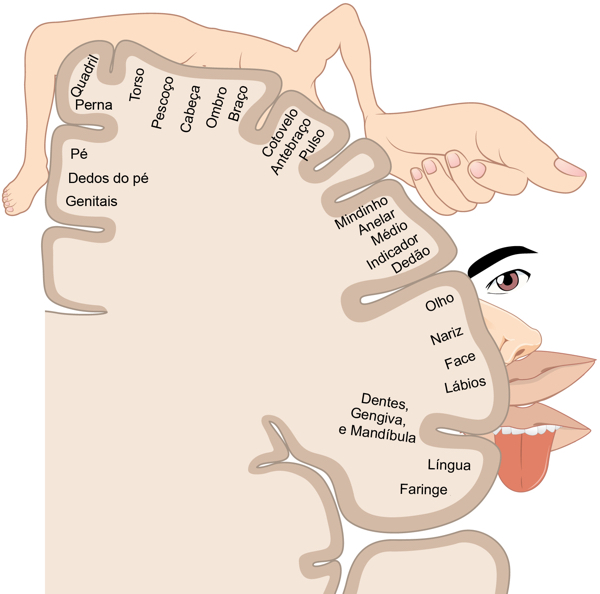

The message travels along the nerve cell up (the ascending pathway) to the thalamus of the brain. The thalamus is another relay station which sends the information to the outer part of the brain that is associated with sensation. This area is called the somatosensory cortex. Different areas of the somatosensory cortex match different areas of the body, letting the brain know where the damage has occurred. There is a descending pathway which actually regulates and modulates the information from the ascending pathway.

With CRPS, normal healing—calling immune cells in the inflammatory process—goes out of control, releasing more inflammatory chemicals than are necessary. Increased swelling takes place. The immune system goes into overdrive and according to Schneider’s CRPS guidebook, “The way your nerves communicate with each other can change, not just in the painful area, but also in your spinal cord and brain. This can make your nerves more sensitive and lead to increased pain.” Your injury heals but the pain remains and may spread.

What is Neuroplasticity?

Neuroplasticity is defined as “a process that involves adaptive structural and functional changes to the brain. A good definition is ‘the ability of the nervous system to change its activity in response to intrinsic or extrinsic stimuli by reorganizing its structure, functions, or connections.’ Clinically, it is the process of brain changes after injury, such as a stroke or traumatic brain injury (TBI).” [5] But it is also something that differs from person to person. As Dr. Lara Boyd, the University of British Columbia Canada Research Chair in Neurobiology and Motor Learning, points out in an early TedX talk on the subject, “The shaping of our plastic brains is far too unique for there to be any single intervention that’s going to work for all of us…. to optimize outcomes each individual requires their own intervention.” [6]

Dr. Schneider agrees. In his video “New Science, Real Hope: How Neuroplasticity is Changing CRPS Care,” he notes that outdated content on the web, “highlights the most difficult and negative things can come with these conditions,” and reduces hope but that “regardless of how long someone has had this condition, it is still possible for improvement.”[4] Recovery from CRPS is possible.

What is TrainPain?

What fascinated me about TrainPain*** is its use of gamification to retrain your brain. Bringing in the skills and knowledge of game designers, physical therapists, and pain researchers, they have created an 8-week program to help those with CRPS. There is also a program for people diagnosed with Fibromyalgia. After learning about CRPS and meeting people living with the condition, it excited me to see a new way of treating this condition.

What do you think?

September is Pain Awareness Month. Are you experiencing chronic pain? If so, how do you cope with it? Do you think tapping into neuroplasticity could help? Please share your ideas and thoughts in the comments below.

**No one at Medivizor is associated with TrainPain.

References:

1 Frare, J. M., Rodrigues, P., Ruviaro, N. A., & Trevisan, G. (2024). Chronic post-ischemic pain (CPIP) model of complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS-I): Role of oxidative stress and inflammation. Biochemical Pharmacology, 116506.

2 Binkley KE Improving the Diagnosis and Treatment of CRPS: Insights from a Clinical Immunologist’s Personal Experience with an Underrecognized Neuroinflammatory Disorder, 2012, J Neuroimmune Pharmacol DOI 10.1007/s11481-012-9376-x

3 Schneider, E. Resources: CRPS Learning Hub https://www.trainpain.com/crps-learning-resources

4 Schneider, E. New Science, Real Hope: How Neuroplasticity is Changing CRPS Care https://youtu.be/2grh9tx4djc

5 Puderbaugh M, Emmady PD. Neuroplasticity. [Updated 2023 May 1]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557811/

6 Boyd, L. (2015). “After watching this, your brain will not be the same” TEDxVancouver. https://youtu.be/LNHBMFCzznE?si=n88oV2G5b9xwKUDC