An outbreak of H7N9 avian (bird) flu was reported March 17 in Mississippi, USA. This variety of bird influenza has not been seen in the US since 2017. [1] According to the World Health Organization (WHO), humans who have gotten this virus in the past have become severely ill. Since 2013, 1568 people have been infected in China, with 616 of them dying of the disease. [2]

Along with this deadly influenza, the US also has another bird flu that’s been circulating since 2022. It infects birds, cows, pets (cats) and has infected humans. It’s called the H5N1 bird flu.

What do the H’s, N’s and numbers mean when referring to flu? So does bird influenza have anything to do with seasonal influenza? Should we be concerned about the bird flu?

Influenza or The Flu

Everyone has had the flu and we usually don’t think much of it, except to complain and wish we hadn’t gotten sick. The influenza comes seasonally, between October and May in the Northern Hemisphere, and April to September in the Southern Hemisphere. Influenza A and B are the flu types that affect humans seasonally. There are also types C and D, but these are not seasonal (D affects cattle).

But there have been influenza pandemics that have killed millions. The 1918 flu infected over 500 million people worldwide and killed 50 million. [3] According to historians, there have been in excess of 14 flu pandemics since 1500 and five since 1900: 1918, 1957, 1968, 1977 and 2009. [4]

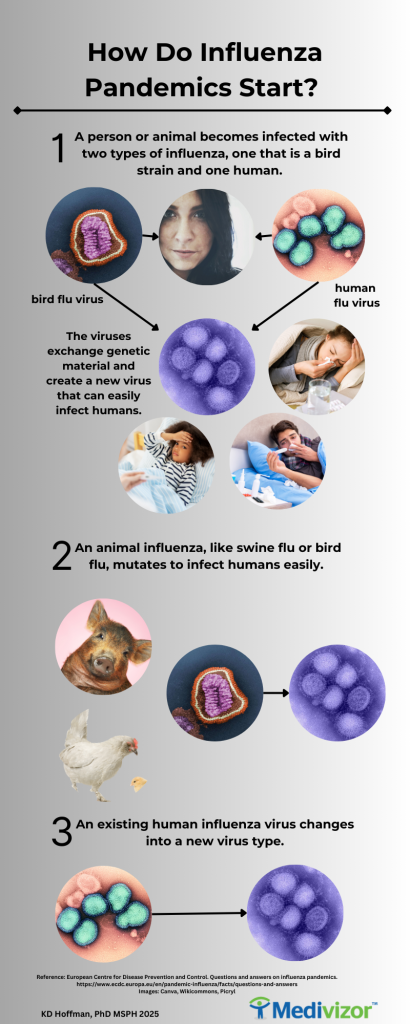

Flu pandemics are caused by Influenza A viruses. According to the CDC, “a pandemic can occur when a new and different influenza A virus emerges that infects people, has the ability to spread efficiently among people, and against which people have little or no immunity.” [5]

H’s and N’s and Numbers

Just like other viruses, influenza viruses are made up of RNA and covered in a protein coat. Influenza is covered in two types of glycoproteins, hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N). Hemagglutinin comes in 18 varieties and neuraminidase comes in 11 varieties. The numbers after the letters tell us what variety of hemagglutinin and neuraminidase is covering the virus. [5]

Bird or avian flu is also covered in these proteins, hence the names H7N9 and H5N1 bird flu that we discussed in the first two paragraphs.

The Importance of H and N

Reassortment is the way that influenza viruses change: this occurs when two different types of virus infect an individual and the viruses swap genetic material.

Our immune system builds up an immune response with antibodies to the glycoproteins H and N (antigens) that cover influenza viruses. Because of this, if we have been sick with flu virus that has an H1N1 cover, we can fight other viruses with H1N1 covers. Even if the new virus has swapped genetic material and its RNA (called RNP) is different from the first H1N1 virus our body fought in the past, our bodies can still mount a defense against the new H1N1 virus. The two H1N1 covered viruses are “antigenically” similar.

What is Antigenic Drift?

As a child, you probably played the game called “Whispers” or “Telephone” where you sit in a circle and one person whispers a phrase in the next person’s ear. Once the phrase is whispered around the circle, the last person reveals what they heard. Often small changes or errors have occurred making the phrase different from what it was in the beginning of the game. Antigenic Drift is like this. The flu virus spreads from person to person, replicating itself as it goes. Errors occur in replication. These changes build up as the flu spreads from person to person and makes the influenza virus less recognizable over time. In fact, the covering of the virus changes so much that our immune system needs help to recognize the virus.

The CDC, NIH and WHO are organizations that track virus antigenic drift over time. With that tracking, these organizations are able to recommend what influenza covering will be most prevalent in the coming flu season. The vaccines that we receive incorporate the changes and errors that have occurred over the course of a year in the flu and make it possible for our bodies to create new antibodies against the flu.

Antigenic Shift and Pandemics

Antigenic Shift is the game of “Whispers” with a twist. Imagine you are playing the game and midway through a round, one of the people in the circle changes the language being used in the game. The game is completely disrupted. This is the kind of change that occurs with a pandemic. [6]

The 2009 influenza pandemic is an example of the reassortment of viruses from pigs, birds and humans. The changes in the protein envelope of the virus were so extreme that the virus was able to evade any antibody responses built up in humans. The virus — an H1N1 type — was a combination of several viruses: the human H3N2, a Eurasian avian-like H1N1, and swine flus from North America and Eurasian pigs. [7]

Since pigs can get bird flu as well as human influenza, they are a great reservoir where different viruses can mix and reassort. This happened with the virus that caused the 2009 pandemic.[8]

Influenza Virus Naming

This mixing and reassortment of the flu virus makes it unpredictable and extremely tricky. Because of this, researchers the world over have had to create a system to name and keep up with them. For example, here is the name of one flu virus: A/Sydney/05/97(H3N2). This name tells us that this is virus type A, found in Sydney, Australia, strain number 5, found in 1997 and of the subtype H3N2. Since this is a virus originating in humans, the name does not include human. If it were found in a duck, the name would be A/duck/Sydney/05/97(H3N2). [8] Much time and energy goes into keeping up with what the wide variety of flu viruses are doing. Without the manpower and willingness of governments to support this type of science, the death toll of the 1918 influenza pandemic would have been repeated in subsequent pandemics.

Recent flu pandemics

The 1918 virus has been linked to a reassortment of an avian flu to humans. Before 1957, an avian virus mixed with that 1918 virus to create a new strain that caused a pandemic. Below is a table listing the most recent flu pandemics.

After a pandemic, survivors have antibodies to that flu virus. The virus becomes endemic — part of the group of seasonal flus that we experience each year. In fact, virus descendants of the most recent pandemics and influenza B viruses circulate during the flu season.

People die every year from the flu but at a lower rate than during pandemics. Vaccination reduces those numbers. Vaccines help us create immunity to the seasonal flu virus but also provide some immunity to potential pandemic viruses, especially those that live in animals and can jump to humans.

| Pandemic year | Area or emergence | Type | Worldwide mortality | Age group |

| 1918-1919 Spanish Flu | Unknown | H1N1 | 20-50 million | Young adults |

| 1957-58 Asian Flu | Southern China | H2N2 | 1-4 million | Children most affected |

| 1968-69 Hong Kong Flu | Southern China | H3N2 | 1-4 million | All age groups |

| 2009 Mexican Flu | Mexico/Southern US | H1N1 | 150-576 thousand | Ages 5 – 30 years old |

The Importance of Virus Research and Vaccine Science

Only fools would think that vaccines do not save lives. As can be seen in the table above, since vaccines have been available, flu pandemics have had fewer deaths associated with them. In addition, the scientists and researchers who monitor flu viruses have been able to predict and supply people with vaccines that work, helping our bodies have enough immunity to the disease that most bouts of influenza are not fatal. If you get the flu, even after getting the vaccine, you get a less lethal experience because your body has had time to build up some crucial immunity!

References

[1] https://www.reuters.com/business/healthcare-pharmaceuticals/us-reported-first-outbreak-h7n9-bird-flu-farm-since-2017-woah-says-2025-03-17/

[2] https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/375483

[3] https://archive.cdc.gov/www_cdc_gov/flu/pandemic-resources/1918–commemoration/1918–pandemic-history.htm

[4] Taubenberger JK, Morens DM. Influenza: the once and future pandemic. Public Health Rep. 2010 Apr;125 Suppl 3(Suppl 3):16-26. PMID: 20568566; PMCID: PMC2862331.

[5] https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/viruses-types.html

[6]Immunize Canada. Why do we need to get a fl u vaccine every year? Answer: drift and shift. https://immunize.ca/sites/default/files/Resource%20and%20Product%20Uploads%20(PDFs)/Campaigns/Influenza/2022-2023/influenza_drift_or_shift_2022_2023_web_e.pdf

[7 ]Jilani TN, Jamil RT, Nguyen AD, et al. H1N1 Influenza. [Updated 2024 Mar 4]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513241/

[8] Kim H, Webster R, Webby R. Influenza virus: Dealing with a drifting and shifting pathogen. Viral Immunology.2018.31:2. https://doi.org/10.1089/vim.2017.0141

[9]European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Questions and answers on influenza pandemics. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/pandemic-influenza/facts/questions-and-answers (see infographic)