The Advent of Public Health

During the first half of the 1800s, something extraordinary happened.

Carried along trade routes and with the movement of troops, the world truly unified, but not in a good way. Bacteria, viruses, and parasites traveled easily and frequently, bringing successive epidemics of plague, yellow fever, and cholera across industrialized countries. Disease brought the world together.

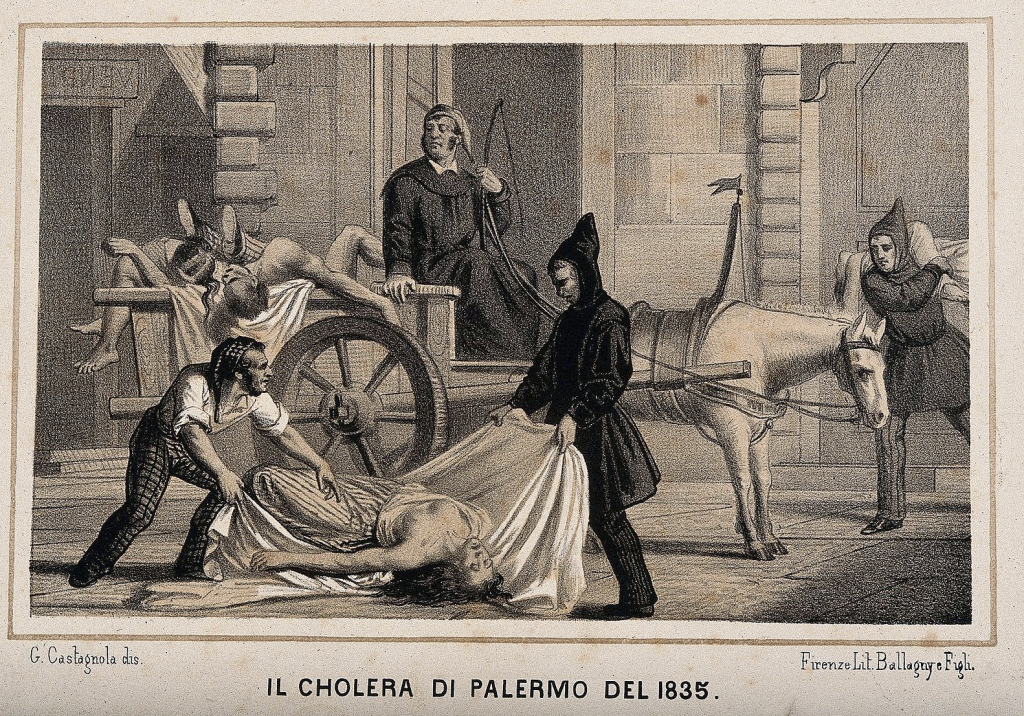

Cholera’s first appearance in Western Europe in the 1820s brought this new reality to the attention of governments. No one could agree on the cause of cholera or on strategies to stop its spread. Finally, in Paris in 1851, diplomats and physicians gathered for the first International Sanitary Conference. [1] Its mandate: to come up with international quarantine regulations against the spread of plague and yellow fever, but especially cholera.

There were a series of these International Sanitary Conferences. In 1881, the United States participated in its first. [2] Through these conventions came an understanding that intelligence and information on diseases must be shared among nations in order to halt their spread.

When aviation became another means of disease transport, the International Sanitary Convention for Aerial Navigation was organized in 1933. By this time, the League of Nations’ health organization became involved. [3] After World War II, in 1948, these conferences had evolved to the World Health Organization (WHO), a specialized health agency of the United Nations. The United States, along with 194 member nations, co-founded the WHO. [4]

Since then, the WHO has been instrumental in dealing with health emergencies, like polio epidemics breaking out in a variety of places across the globe, the eradication of smallpox, and the public health tracking of outbreaks like COVID.

WHO helps industrialized nations, but also those suffering in undeveloped countries.

The Symbol of Medicine: The Guinea Worm

Former President Jimmy Carter, speaking to the House of Lords in 2016, explained why it is important to help other countries with diseases:

There are very practical reasons for alleviating the suffering of people in other countries. First of all, it keeps the disease from affecting ourselves and those we love. It advances science and technology. It supports commerce and economic development. And it’s also very efficient. These are all good, practical reasons. And it’s also the right thing to do to share our knowledge, experience, and science with those who need our help to improve their own lives. It’s also an act of kindness, a recognition of our common humanity.

The Carter Center

President Jimmy Carter – Lord Speaker’s Global Lecture Series

February 3, 2016 https://www.cartercenter.org/resources/pdfs/news/editorials-speeches/President-Carter-House-of-Lords-Presentation.pdf [emphasis added]

His presentation focused on the work of the Carter Center alongside the WHO, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) among others to eliminate a horrible parasite called the Guinea worm. [5]

This parasitic worm, a female nematode named Dracunculus medinensis (meaning the ‘little dragon of Medina’) has been around for thousands of years: the worm has even been found in Egyptian mummies. These parasites can grow as long as 1 meter (around 3.3 feet). People get them from drinking stagnant water.

The main hosts for this parasitic worm are humans but the intermediate hosts are micro-crustaceans related to shrimp living in brackish or stagnant water. A person drinks the crustaceans and the worm larvae are released into the human gut. In the gut, the worms grow and mate. The females migrate to the person’s lower limbs where they continue growing to their full length. When fully grown, they burn through the skin creating painful, searingly hot, blisters. It takes weeks for them to leave the body. To alleviate the pain, the person bathes in water. The cool water triggers the female worm to release her larvae into the water and its life cycle begins again. [6,7 ]

There is no medicine to treat this condition. Secondary bacterial infections occur around the site where the worm leaves the body. The only treatment, which has been used for thousands of years, is winding the worm around a stick to get it out faster. In his presentation to the House of Lords, President Carter explained:

It’s believed that this inspired the symbol for medicine. A lot of people think that it’s a snake that’s kind of wrapped around a rod. It’s actually a Guinea worm wrapped around a stick. This is the Staff of Asclepius, which is now the basic symbol for medicine itself. So it’s an ancient disease, and a symbol for the entire medical profession is the treatment of Guinea worm.

The Carter Center

President Jimmy Carter – Lord Speaker’s Global Lecture Series

February 3, 2016 https://www.cartercenter.org/resources/pdfs/news/editorials-speeches/President-Carter-House-of-Lords-Presentation.pdf [5]

From the Staff of Asclepius to Public Health

In public health, researchers, practitioners, and educators prevent disease and injury at the community and population level. We identify the causes of disease and disability, and we implement large-scale solutions.

For example:

Johns Hopkins School of Public Health website: https://publichealth.jhu.edu/about/what-is-public-health [8]

- Instead of treating a gunshot wound, we work to identify the causes of gun violence and develop interventions to prevent it.

- Instead of treating premature or low birth-weight babies, we investigate the factors at work and we develop programs to keep babies healthy.

- Instead of prescribing medication for high blood pressure, we examine the links among obesity, diabetes, and heart disease—and we use data to influence policy aimed at reducing all three conditions.

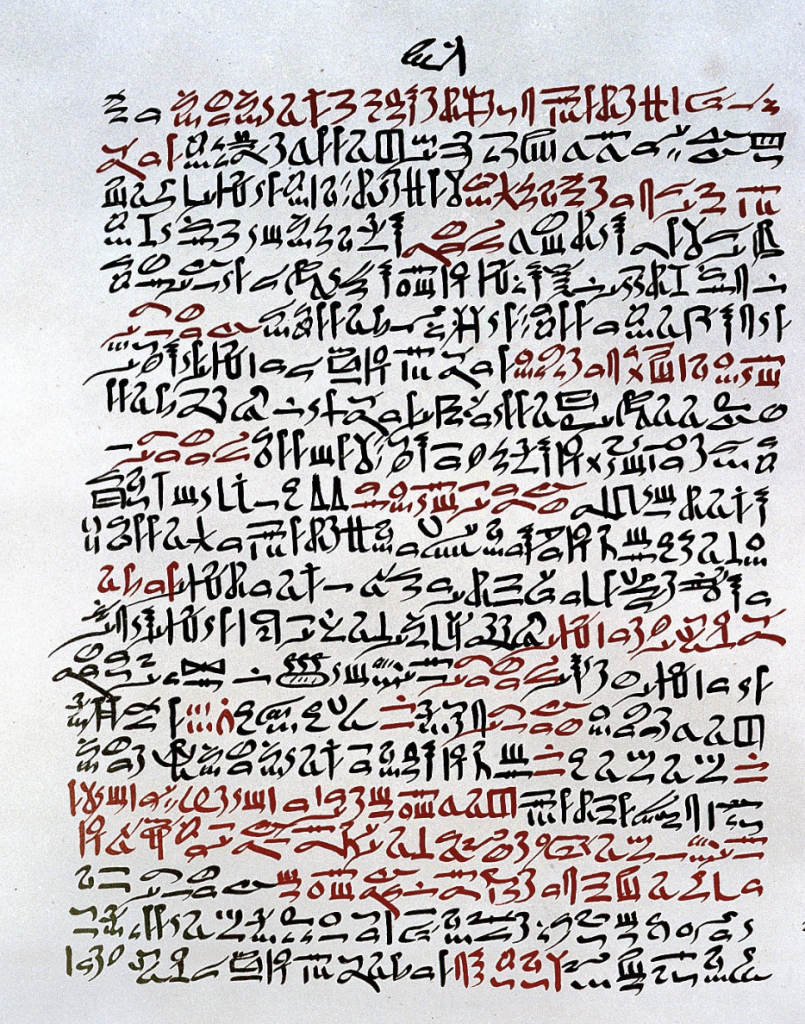

There have been large scale efforts throughout history to implement disease prevention. Sanitary efforts to prevent contamination of water by sewage are described in Egyptian papyrus, Hebrew Mosaic law of the five Books of Moses, and in documentation from Chinese, Indian, Greek and other societies.[9]

Efforts continued into more recent times. Pasteur’s work in developing rabies vaccines and pasteurization marked a turning point in understanding germs (the germ theory) and building public health strategies like vaccines to prevent disease.

Rabies was widely feared as a disease transmitted to humans through the bites of infected animals, and was universally fatal. Pasteur reasoned that the disease affected the nervous system and was transmitted in saliva. He injected material from infected animals, attenuated to produce protective antibodies but not the disease. In 1885, a 14-year-old boy from Alsace was severely bitten by a rabid dog. Local physicians agreed that because death was certain, Pasteur, a chemist and not a physician, be allowed to treat the boy with a course of immunization. The boy, Joseph Meister, survived, and similar cases were brought to Pasteur and successfully immunized. Pasteur was criticized in medical circles, but both the general public and scientific circles soon recognized his enormous contribution to public health.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7170188/#s0065 [9 ]

The International Sanitary Conferences were a culmination of hundreds of years of work and their successors, the WHO and the CDC continue that profoundly important labor.

The WHO and the CDC are public health institutions. Their history and that of public health is about searching for ways to prevent disease in populations and keeping people across the world healthy.

As COVID-19 so effectively demonstrated to the world, a disease that is easily transmissible—spread through the air, for example—can spread from one small place in China to all over the world.

But that is not all. Parasites, like the guinea worm, can spread to other countries through travel. Or in situations where sanitation fails, like a place that experiences flooding, diseases that are not usually seen in industrialized countries can and do occur. In a statement released in January, the WHO tried to explain some of what it does to help people in industrialized countries and around the world:

“Every day and through the night, teams of WHO experts sift through thousands of pieces of information, including scientific papers and disease surveillance reports, scanning for signals of disease outbreaks or other public health threats, from avian flu to COVID-19.

WHO mobilizes to prevent, detect, and respond to infectious disease outbreaks while also strengthening access to essential health services.

That includes bolstering hospital capacity to do everything from delivering new babies to treating war injuries and training healthcare workers.”

https://news.un.org/en/story/2025/01/1159266 [10]

Like WHO, the CDC mobilizes to prevent infectious disease outbreaks. It is at the cutting edge of research to keep the population of the US health. It provides physicians in the US with up-to-date information on caring for children and adults. That information is crucial to supporting healthcare providers, pharmaceutical companies who create our medications and treatments, researchers, and educators. It is involved in constant monitoring of health threats.

When the WHO and the CDC are in their element, they head off infectious disease before it even gets started. Absence of awareness about their work is a sign of their success. Through information sharing among governments, crises are averted. Moreover, governments and private sector entities—from charitable foundations to health insurers—use WHO and CDC information to maintain the high standards of population health we have come to expect throughout the developed world.

References

[1] Huber, V. (2006). The Unification of the Globe by Disease? The International Sanitary Conferences on Cholera, 1851-1894. History The Historical Journal, 49, 2. pp. 453–476 https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/41107830/Huber2006UnificationoftheGlobebyDisease-libre.pdf

[2 ] Cummings, 1926. The International Sanitary Conference. American Journal of Public Health. 16(10). https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/pdf/10.2105/AJPH.16.10.975-a

[3] Sanitary Arial Navigation Treaty 1933. Library of Congress. https://maint.loc.gov/law/help/us-treaties/bevans/m-ust000003-0089.pdf

[4] World Health Organization. WHO History. https://www.who.int/about/history

[5] Carter, J. (2016, February 3). The Carter Center. President Jimmy Carter – Lord Speaker’s Global Lecture Series

https://www.cartercenter.org/resources/pdfs/news/editorials-speeches/President-Carter-House-of-Lords-Presentation.pdf

[6] Simonetti O, Zerbato V, Di Bella S, Luzzati R, Cavalli F. Dracunculiasis over the centuries: the history of a parasite unfamiliar to the West. Infez Med. 2023 Jun 1;31(2):257-264. doi: 10.53854/liim-3102-15. PMID: 37283632; PMCID: PMC10241402.

[7] Guinea Worm. Museum of American History. https://www.amnh.org/explore/science-topics/disease-eradication/countdown-to-zero/guinea-worm

[8] Johns Hopkins School of Public Health website: https://publichealth.jhu.edu/about/what-is-public-hea

[9]Tulchinsky TH, Varavikova EA. A History of Public Health. The New Public Health. 2014:1–42. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-415766-8.00001-X. Epub 2014 Oct 10. PMCID: PMC7170188.

[10] Travers, E. (2025, January 21). What is the World Health Organization and why does is matter? United Nations: UN News. https://news.un.org/en/story/2025/01/1159266