The sun is shining and there’s a cool breeze from the south. At the 16th mile mark two  townships meet and a 200 year old bright white church sits at the juncture. Here the old stone walls make a perfect place to sit and watch the event unfold on the street. Vendors sell flags and noisemakers, loaded down pizza delivery men search for the customers who called in, children sit on the ground behind a yellow rope scooting closer and closer to the boundary to be the first to see.

townships meet and a 200 year old bright white church sits at the juncture. Here the old stone walls make a perfect place to sit and watch the event unfold on the street. Vendors sell flags and noisemakers, loaded down pizza delivery men search for the customers who called in, children sit on the ground behind a yellow rope scooting closer and closer to the boundary to be the first to see.

Suddenly, along with the rustle of trees, songs of cardinals, blue jays and robins, the hubbub of children’s impatience and parents’ encouraging “It’s starting soon,” there is a change. A wave of sound rolls along the route, indistinct at first, then clearer as it approaches. “There,” someone shouts, as the applause, cheers and ringing cowbells pour toward you. Low to the ground, speeding down the hill, it approaches. The metal flashes as two arms and a head come into view and the push rim racing division zooms by in their modified wheelchairs. Over and over the pattern continues, sound and the watching crowd curl at the pace of the race and the racers.

Going the Distance

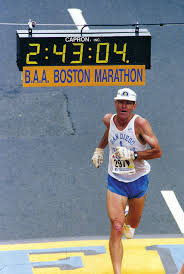

At 72, Hal Goforth** says he has over 100,000 miles on his body. Since 2016 is his 40th running of the Boston Marathon, there’s no doubting his veracity. But nothing in his self effacing demeanor prepares the listener for the expert stream that pours forth on the topic of marathon preparation. A researcher in physiology, Goforth conducted research to enhance the endurance of Navy Seals and Marines. Elite runners and sports enthusiasts use interventions with caffeine, hydration solutions and training techniques Goforth tested. For example, caffeine actually increases the endorphins in the body and makes exercise feel easier, less effortful. He recommends the caffeine (in the right dose) 60 to 90 minutes before exercise.

At 72, Hal Goforth** says he has over 100,000 miles on his body. Since 2016 is his 40th running of the Boston Marathon, there’s no doubting his veracity. But nothing in his self effacing demeanor prepares the listener for the expert stream that pours forth on the topic of marathon preparation. A researcher in physiology, Goforth conducted research to enhance the endurance of Navy Seals and Marines. Elite runners and sports enthusiasts use interventions with caffeine, hydration solutions and training techniques Goforth tested. For example, caffeine actually increases the endorphins in the body and makes exercise feel easier, less effortful. He recommends the caffeine (in the right dose) 60 to 90 minutes before exercise.

Marathons require hydration. Goforth has studied hydration pre and post exercise, using water and a high-sodium solution (like Gatorade). Those subjects who merely consumed water were dehydrated three hours after their workout. Those who drank the high-sodium solution retained 35 percent of the fluid—they became hyper-hydrated. Of course, hyper-hydrating is not for everyone and should only be used under the direction of a physician. But it has worked for Goforth and many marathoners over the years.

Changes In the Marathon

One hundred twenty years is a long time. Much has changed since the beginning of this race. Fifteen men ran the race in 1897. Thirty thousand (30,000) ran yesterday’s race. The first woman ran 50 years ago this year. At that time, according to the Amateur Athletic Union, women could not run longer than 1.5 miles. Bobbi Gibb sneaked onto the course near the starting line in 1966 wearing a hoodie over her pony tail and her brother’s shorts in an attempt to blend in. Not long after though, her fellow racers figured it out. They supported her run, protecting her from being thrown out and vouching for the fact that she completed the race in 3 hours 21 minutes as she crossed the finish line.

Fifteen men ran the race in 1897. Thirty thousand (30,000) ran yesterday’s race. The first woman ran 50 years ago this year. At that time, according to the Amateur Athletic Union, women could not run longer than 1.5 miles. Bobbi Gibb sneaked onto the course near the starting line in 1966 wearing a hoodie over her pony tail and her brother’s shorts in an attempt to blend in. Not long after though, her fellow racers figured it out. They supported her run, protecting her from being thrown out and vouching for the fact that she completed the race in 3 hours 21 minutes as she crossed the finish line.

The wheelchair division started in 1975 with one wheelchair completing the marathon. Qualifying times and a prize purse make this an elite event for push rim racers. In the 1980’s a mobility impaired and visually impaired/blind division were added to the marathon.

Boston Strong

There are many stories of strength. For example, Patrick Downes and Adrianne Haslet-Davis ran and finished this year’s race. They are survivors of the 2013 Boston Marathon bombings. Running on prosthetic blades, they completed the 26.2 miles in 5 hours 56 minutes and 46 seconds and 10 hours, respectively.

But the most important part of this event are the people. People from all over the world participate in the Boston Marathon. They come a long ways to run a long distance, together.

**Conversation with Hal Goforth, PhD April 17, 2016