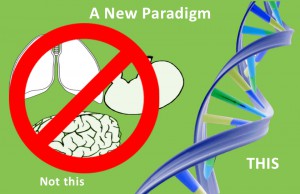

We’ve gotten used to thinking about having cancer in your colon or lung or breast. We’ve systematized treatments and research of cancer by the organ that’s affected. And we’ve been fundraising that way too–pitting lung cancer against breast cancer against childhood cancers. But what if this view of cancer is totally wrong?

We’ve gotten used to thinking about having cancer in your colon or lung or breast. We’ve systematized treatments and research of cancer by the organ that’s affected. And we’ve been fundraising that way too–pitting lung cancer against breast cancer against childhood cancers. But what if this view of cancer is totally wrong?

That’s the question that is driving a new direction for NCI and researchers around the US. The new focus is on genes and how those genes influence the out-of-control, immortality of cancer cells.

A New Look At Outliers

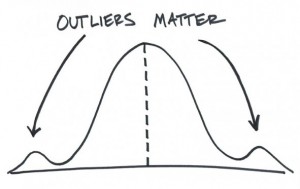

The way research usually works is to concentrate on statistical significance: the search for confidence that something that you did made a difference and that it probably wasn’t just blind luck that caused it to happen. The number that is used to test this is the average or mean.

Let’s look at an example. Say a new medication is tested and it doesn’t work on most of the people who take it. Often that medication gets put on the shelf. But, what if there are some people who took the medication and had a miraculous recovery? In statistics, those people are outliers…and though everyone is happy for their success, researchers have usually ignored them.

Now, what if there was a way to find out why those miracles happened? In an initiative described in NCI’s press release last fall,

“investigators will study the molecular characteristics of tumors of patients who had an exceptional response to a cancer therapy. In doing this, they hope to discover molecular features in the tumors that may predict benefit to a particular drug or type of drug.”

A Washington Post article describes how this type of research can have an enormous effect on someone’s life. Review of data on a “failed” medication led to a woman with thyroid cancer who had a miraculous recovery. Genetic sequencing of her tumor led to the discovery that she had a mutation in the gene that regulated a protein pathway that allowed her cancer to grow. The “failed” medication inhibited that protein pathway.

Physicians at Dana Farber Cancer Institute looked in their database for other patients with that mutation. There were several. One, a patient with advanced ovarian cancer, received treatment with the “failed” drug and her cancer is in remission.

Patients as Partners

Corrie Painter, PhD, (who we introduced here) is a mother, scientist and patient advocate. In a previous life, she was headed for a tenure track position with a lab in Biochemistry. After walking away from a million dollar grant, she has taken a position at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard as their Associate Director of Operations and Scientific Outreach. There she is using her experiences as a patient to initiate direct partnerships with patients. The goal of the work she is doing is to accelerate discoveries and treatments for cancers through collaboration.

previous life, she was headed for a tenure track position with a lab in Biochemistry. After walking away from a million dollar grant, she has taken a position at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard as their Associate Director of Operations and Scientific Outreach. There she is using her experiences as a patient to initiate direct partnerships with patients. The goal of the work she is doing is to accelerate discoveries and treatments for cancers through collaboration.

“Imagine what would happen if there was ample preliminary data for all scientists to share. Those scientists could write grants based on their ability to synthesize the most amount of information based on a robust and shared knowledge base,” Corrie wrote.

The first project, #MBCProject, was introduced on the #BCSM website. The #MBC stands for metastatic breast cancer and the project is a new Broad Institute and Dana Farber Cancer Institute research initiative designed to accelerate discoveries and treatments for breast cancer metastases. The project is being done in partnership with advocacy groups like the Metastatic Breast Cancer Alliance, the Metastatic Breast Cancer Network, the Avon Foundation, Living Beyond Breast Cancer, the Young Survival Coalition, and the Inflammatory Breast Cancer Research Foundation.

Wait! Isn’t This Organ Based Research?

Why start by studying metastatic breast cancer? Corrie answered this way. First, “the study of extraordinary responders in and of itself will be a game changer for treating cancers by mutation.” Second, research specific to metastatic breast cancer has been limited. Third, since most patients in the US receive care at non-research facilities, their tumors are never studied. “By reaching out to patients online we will be able to work with people all over the country regardless of where they live.” Fourth, “we need to understand the mutations in the context of their biology and clinical behavior, and then we’ll have the infrastructure

to understand how to treat cancer by mutational profiles rather than simply by site of origin.” Finally Corrie explains, “we hope to move the needle on both fronts by performing a number of studies in mbc, leading with extraordinary responders.** Our goal is to partner with patients, conduct research and listen to their…voices, [to] pave a path forward by learning [from] both directions.”

A website is under construction that will allow any patient with metastatic breast cancer to sign up. After signing up, the plan is to obtain medical records, tumor samples and saliva. Genetic analysis will be conducted on the tumors and saliva. But this work will not occur in a vacuum: patients are collaborators in this research.

Changing The Culture of Academic Research

Having been an academic researcher, Corrie knows the culture. “Every lab needs to establish an independent area of expertise. To publish, you need to discover or describe something that no one else has figured out. Think that happens by scientists talking openly and collaboratively about their ideas? Nope.” Being “scooped” is the fear of academic medicine. ” You can get scooped by scientists who hear about your unpublished work at conferences, by word of mouth, by “collaborators”, by reviewers who are reading your manuscript (by far the most nefarious). Best way to not get scooped? Work in a little silo and keep your data SECRET until publication.”

This culture brings publications and facilitates the climb from non tenured assistant professor to full tenured professor with a well-funded lab and many graduate student workers, but does it save lives? Corrie answers with a resounding NO. “We can redefine the way that science is “tackling” cancer. When scientists care more about high impact papers, and getting tenure than they do about curing disease, it’s UNACCEPTABLE.”

Patients Included In Research

As a patient and a scientist, Corrie’s perspective was sought out by the Broad Institute. The innovation is “patients included.” This is not just at conferences, but also on the research bench. The goal is shared data, collaboration and breakthroughs. Targeted therapies that are not organ-specific but are genetic-mutation specific are pushing this movement.

Corrie is hopeful, “Technology has reached a point where we can ask questions like, “what drives my cancer, why did I develop resistance to a targeted therapy, what combination of drugs might work best for me?” And when I say it in the first person, I mean it…from the patient, for the patient. And this brings me to my favorite point with respect to progress in cancer research. THE PATIENT IS BEING LISTENED TO.”

Metastatic breast cancer is just the beginning. Corrie and the Broad Institute are interested in making this kind of collaboration a reality with other cancers as well. Corrie states, “Our goal is to generate enough of an understanding of cancer at the crossroads between traditional site- specific studies and genomics that cancers will one day be treated by their mutational profiles rather than their site of origin.”

For more information email at info@MBCproject.org

**Correspondence with Corrie

If as the article states that the view of cancer based on location it started might be wrong, why are Broad Institute researchers organizing their work one cancer at a time starting with breast cancer? Why not focus starting with mutations that are similar across tumor locations (such as BRCA mutations that when you include somatic BRCA mutations are found in numourous types of cancer)? Particularly when looking at metastatic cancer that by definition has left the organ where it started this would seem to be a more logical aproach.

Hi Ken,

You’ve raised some great questions. I communicated with Corrie and I have added a paragraph with some answers. I hope this helps. Thank you for commenting. Best, Kathleen

Hi Ken,

I’m not sure the take away here is that studying organ specific cancer is wrong, but rather that there could be somatic mutations driving cancers that are targetable, and that we are going to try and build a knowledge base of information that couples these clinical responses with genomic information. We are going to study extraordinary responders in metastatic breast cancer and then branch out, as Kathleen alluded to. Our approach is to start with a therapy that shows efficacy in a small subset of patients, try and figure out why they had that response and then use that information for other patients who may have different cancers but the same genomic drivers that are targettable. Happy to discuss further if you’d like. Thanks for the great question!

Corrie and Kathleen – Thanks for expanding on the initial article. To be clear, my point was not that studying organ specific cancer is wrong, just that we clearly need to be looking at it from the other direction (mutations that cross cancer types) at the same time.

Cleary there are many obstacles to shifting treatment of cancer based on mutations and it is great to see that Corrie and others and doing research that are leading this transition. Besides the research obstacles there are regulatory obstacles as some of these treatments already exist and are not available since FDA approval is tied to cancer type and not mutation ( the PARP inhibitor that is approved for BRCA mutated ovarian cancer is not approved for other BRCA mutated cancers).

Those of us with metastatic cancer (I have both an inherited BRCA1 mutation and a somatic BRCA2 mutation in my cancer that started in my bladder) are just a little impatient that our “cancers will one day be treated by their mutational profiles” when it is clear that that day is still in the future and not now.

Thanks so much for this reply and your efforts. I’m very glad that we are shedding light on the process and results AND by discussing the research process. Let’s keep this up! Kathleen

Ken, I empathize completely with your need for urgency and the frustrations that must come along with knowing there are valid treatments that are not offered because of regulation. I agree 100% with what you said. I hope very much to provide more evidence to the growing data that will be needed in order to bring about these much needed changes.

My sister has atypical chronic myeloid leukemia. She did not have the mutation they were looking for on her red cells so her doc told her there is no particular drug that will put her in remission and will just treat her for quality of life. He gave her a year but she seems to be doing fairly well on the chemo he chose. I would like to know if you know of any research going on for this type or if you could tell me how to look for such. Thank you so much for what you are doing.

Sincerely,

Bonnie Winslow, RN

How does a patient enroll in this trial?

Karen, which specific trial are you referring to?

For information on the #MBCproject discussed in the post, write to Corrie Painter, PhD at info@MBCproject.org

A website is in development and we will let you know via this blog when it is up and running.

Thank you Dr. Painter for standing up and stepping out in an initiative to shift the traditional protocols of all cancers that are very ineffective in alot of cases, and money continued to pour in large amounts to non effective treatments and drugs. Drugs that we are dying from the side effects not the cancer. I also can appreciate where you have to start this initiative to gain the most participants and build the infrastructure needed to understand how to treat cancer by mutational profiles rather than site of origin. Collaboration between patients, shared data, research scientist, clinical trials, conferences and sharing together one common goal “curing cancer” wow what a concept. I am being a but smart in my above statement, but come on professionals get over yourself and your success and work together for the solution. I’m glad you explained why starting with breast cancer and understanding mutations, because as a patient diagnosed with alveolar soft part sarcoma and sarcoma as a whole affecting only 15,000 annually I become resentful at times watching money poured into all the household cancer names and things not getting much better. We lack the funding and awareness of rare disease cancer and with few affected you begin to feel as your life doesn’t matter to the big power of govt, where grants and donors give when our prognosis is poor and treatment options and resistance to normal cancer protocol and sarcoma not at a point where you are ever cobsidered

Hi Kristi, Dr. Painter understands having a rare cancer; she is a 5-year angiosarcoma survivor. Here is a post on her activism in supporting and helping others with this rare disease: Angiosarcoma Awareness: Bridging Barriers Online. She understands. Best, Kathleen

Thank you for your response. That’s great with the angiosarcoma awareness page. I am a part of a lot of sarcoma FB pages. I have only found one adult diagnosed with ASPS from Alaska. She was diagnosed 8 years ago. I also knew of a girl who was 15 but passed away just a few months ago. I sent my message previous before I was finished. But I am not going to go back and remember what I was going to finish with. However I am grateful she and others are looking at different ways for research and collaboration amongst many communities to make change possible. I started a non-profit in July for sarcoma research as there was little you can find and lack of funding. Our first charity fundraiser is coming up in March. Thank you

Excellent! Thank you and keep us posted on your non-profit. Take care, Kathleen

So glad to hear Dr. Painter is 5 years cancer free angiosarcoma. I have been trying to spread awareness sarcoma as a whole. Always love to hear clear scans. 🙂