Cancer Research and Money

Funding has been stagnant for years– that’s what the fact sheet of the National Cancer Institute says. This is the federal agency charged with finding a cure for cancer through research. The $4.9 billion per year is spread across a spectrum of cancer investigations, each cancer getting a designated amount.

What if this system is flawed? Critics with valid concerns about Federal funding decisions abound. One is a childhood cancer advocate, Jonathan Agin.

For the love of a child

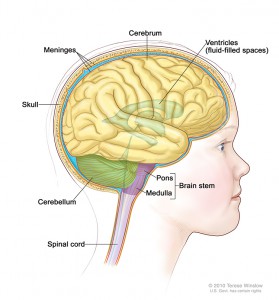

In 2008, Jonathan and his wife Neely’s lives changed forever when Alexis, their 2-year-old daughter, was diagnosed with diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma or DIPG. DIPG is  a cancer of the brainstem, a cancer that cannot be removed surgically. Treatment is palliative; meaning care is given to keep the child pain-free and symptom-free until she dies. Fewer than 10 percent of children with DIPG are alive 2 years after diagnosis. Sadly every year, three hundred children are diagnosed with DIPG in Europe and the US.

a cancer of the brainstem, a cancer that cannot be removed surgically. Treatment is palliative; meaning care is given to keep the child pain-free and symptom-free until she dies. Fewer than 10 percent of children with DIPG are alive 2 years after diagnosis. Sadly every year, three hundred children are diagnosed with DIPG in Europe and the US.

Jonathan and Neely wrote about it on CaringBridge over the next 33 months as Alexis grew, played, laughed and endured treatments and scans. Advocacy, research, monumental effort, hope, despair and scanxiety are part of their story as well as seeking treatment from several physicians and institutions. Alexis died just before her 5th birthday.

Jonathan is a lawyer by training, but he has become a speaker, writer, lobbyist and advocate for increasing funding for research on childhood cancers.

Jonathan is a lawyer by training, but he has become a speaker, writer, lobbyist and advocate for increasing funding for research on childhood cancers.

“I got involved in the fight only because of my daughter Alexis. Childhood cancer was not on my radar screen, but for her diagnosis I would not be involved in this fight. Since her passing in 2011, I have dedicated myself completely.*”

Less than 4%

Every year, around 15,780 US children are diagnosed with cancer. Even though it is the “highest cause of death next to accidents*” and “the number 1 disease killer of children in the US,*” funding for research on all childhood cancer is a little under $200 million or 3.8% of the NCI budget. “Federal investment in childhood cancer research continues to shrink as additional budget issues impact the overall funding,*” Jonathan notes.

One of the reasons given for this low figure is the statistic that childhood cancer has an 80% cure rate. “The 80% figure is the most misleading statistic. Yes, 80% of kids are cured but if you remove the 94% cure rate for ALL [acute lymphocytic leukemia] you would see stats shrink. Many forms of childhood cancer have had 0 advances in over 30 years like DIPG…*” The fact that “over 90% of kids who are ‘cured’ have life-long acute health problems, secondary malignancy and high death rate*” is not included in any “cure rate” figures.

The low numbers also don’t reflect the enormous loss of life-years with each child’s death. “Kids with cancer who die, lose 70 years of life on average.*” Jonathan states.

Ideas for Improving Research

President Obama’s Precision Medicine Initiative recognizes some of the exciting research into an understanding of genes, the individuality of illness and the need for improvement of care. $215 million is the first allocation of funds for the “patient-powered” initiative. This fits with what we know about cancer, it’s as individual as the person who has it. “We need to fight against genetic targets and markers…Not look at cancer in a vacuum but rather as a genetic disease,*” Jonathan believes. “By treating genetic mutations and targets that are similar across cancer types, I believe we can make better impacts.*”

Silos, Business Mindset and the FDA

Jonathan’s advocacy has included numerous Huffington post articles. A series published in 2013 identified problems and delineated a strategy to move the research agenda for childhood cancers further. These problems are occurring in research on treatment for adult cancers as well.

1) “Perception of low patient population”

For-profit pharmaceutical corporations are wary of “low patient populations.” Convincing them of more uses for the drugs, perhaps with other cancers, is crucial.

2) “Partner funding with drug manufacturers to obtain the compounds for testing in labs.”

Barriers are interfering with translation from the lab to the clinical setting. “The reason for slow pace of getting drugs for research,” Jonathan wrote, “is if a drug fails in a research setting, that could suggest that the drug will not be viable in patient trials. Therefore, manufacturers are afraid to allow further testing and release compounds.”

To address this barrier, Jonathan has started a new organization called the Children’s Cancer Therapy Development Institute. Its mission is “to bridge scientific discovery and initiation of clinical trials…seeding Pediatric Phase I and Phase II trials.”

3) Reduction of silos by funding collaborative grants across institutions

In the case of both federally funded and privately funded research, there has been a problem of lack of collaboration and communication. Many parents start not-for-profits in their children’s names to honor them. Organizations, like St Jude’s and The Jimmy Fund, bring in a great deal of money. Unfortunately “the money is being put towards duplicative and single silo research.*” Duplication and redundancy do not create forward movement. Jonathan wrote, “The days of single institution funded grants should be winding down or limited.”

4) Increase involvement in the Patient Representative Program at the FDA.

It is important for childhood cancer advocates to be at the table at the FDA to explain what is happening to real people. Patients and their caregivers can describe life with cancer–with no alternative treatment–better than anyone else.

5) ”Fast track compassionate use—provide investigational drugs outside of a trial”

As Jonathan wrote, “For those of us in the childhood cancer community who are provided with little to no hope, we must be granted every opportunity to try and save our child. The regulatory scheme in place at the present time is not assisting our children in fighting their battles. (Try understanding these regulations.)” If it is hard for an attorney to understand the regulations, imagine the experience of lay person.

A Loss You Don’t “Get Over”

Jonathan describes it this way

“When you lose a child, so much hope escapes with this loss. The

hope of your child growing up, going to college, playing sports, marrying and having children of their own, it is all lost. Why would I want to “get over” the loss of my child? I will never “get over” my child. She was a part of me.”

Parents and caregivers who lose loved ones are uniquely motivated to find new ways to make systems work. Their efforts deserve our attention.

“Alexis never gave up and I won’t either.*”

*Indicates quote from #HCHLITSS tweetchat February 19, 2015