Reviewing history fascinates, educates and can really make you appreciate. That’s what happens when reading about life in the 1800s and early 1900s.

Mystery Meat?

In 1904, the meat packer’s union in Chicago went on strike. At the time four companies ruled the meat-packing world. To end the strike, the companies brought in replacement workers. The uproar and unrest brought a young novelist, Upton Sinclair, to Chicago. He interviewed workers and their families and wrote the book, The Jungle. This fictionalized version of what Sinclair saw and experienced included descriptions of the filthy, unsanitary conditions in the meat packing plants: diseased, rotten and contaminated meat products were processed and labeled for sale, workers with tuberculosis spit up blood, coughed on meat, meat for canning was piled on floors covered in human urine, spit, rat dung and dead rats. Men fell into lard vats and became part of the lard that was sold. The book was a sensation and gives a whole new meaning to the phrase Mystery Meat.

Patent Medicines?

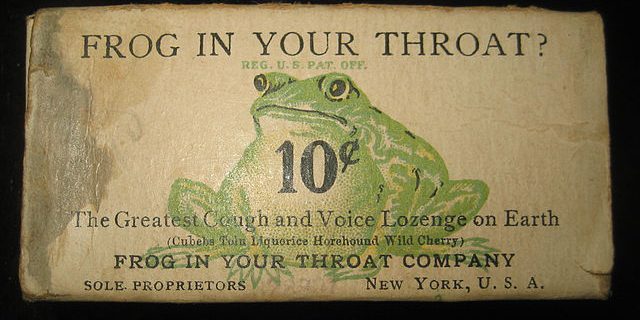

Implementation of the scientific method led to the discovery of a few herbal remedies that were actually effective in helping patients. But they were inadequate for dealing with the multitude of diseases. This led some to attempt to create medicines that could deal with those many diseases and symptoms.

Implementation of the scientific method led to the discovery of a few herbal remedies that were actually effective in helping patients. But they were inadequate for dealing with the multitude of diseases. This led some to attempt to create medicines that could deal with those many diseases and symptoms.

Solar Tincture “restores life in the event of sudden death” and other 19th C nonsense.

Elixirs like Solar Tincture were one of the first projects of advertising. Advertisers promoted and promised everything from the prevention of venereal diseases to curing cholera, epilepsy, scarlet fever and “female complaints.” In 1905, Samuel Hopkins Adams wrote “The Great American Fraud,” an expose in Colliers Magazine.

“Gullible America will spend this year some seventy-five millions of dollars in the purchase of patent medicines. In consideration of this sum it will swallow huge quantities of alcohol, an appalling amount of opiates and narcotics, a wide assortment of varied drugs ranging from powerful and dangerous heart depressants to insidious liver stimulants; and, in excess of all other ingredients, undiluted fraud.”

This was the world of food and medicine prior to the Pure Food and Drugs Act of 1906. Yet there were no laws requiring manufacturers to demonstrate a medication’s safety. This changed in 1937 when 107 people died after ingesting “elixir sulfanilamide,” a patent medicine made of, among other things, diethylene glycol, a renal and neurologically toxic industrial solvent. Tragedy spurred action and in 1938 The Federal Food Drug and Cosmetic Act passed the US Congress. The Act required manufacturers to prove the safety of drugs, established rules for advertising, labeling and launched the use of prescriptions to obtain medications.

Transitioning from a farm to industrial economy, human greed took precedent over public health. Implementing the scientific method, imposing sanitation and rules upon manufacturers saved lives.

With this backdrop in our next part of this post, we’ll review the present-day medicine approval process in the US.