It has taken decades of work for researchers to find ways to activate the immune system to treat cancer (what we now call immuno-oncology or I-O). Much of that work has been poorly funded. Largely, it has been the result of researchers getting experience in other disciplines (like infectious disease) and then transferring that expertise to oncology research. And often it has been the result of sharing among  researchers at a variety of academic and government institutions as they puzzled and worked to solve complex questions.

researchers at a variety of academic and government institutions as they puzzled and worked to solve complex questions.

Carl June, MD is one of those scientists. In a recent interview on CureTalk, Dr. June discussed how CAR T-cell therapy works and how the tools he needed for his success evolved through the vagaries of his work history.

Technique 1: Growing T-cells Outside of the Body

Dr. June started out in the Navy in the 80’s, working in oncology on bone marrow transplants. Bone marrow transplants require high dose chemotherapy to eliminate the patient’s own marrow. Then marrow from a donor is injected into the patient.

One problem patients experienced was severe side effects called graft versus host disease where the donated bone marrow created immune cells (T-cells) that attack the recipient’s body. To address this side effect, Dr. June conducted research to learn how to grow T-cells from the patient so that there would be no need for donor marrow, so the cells could come from the patient.

Technique 2: Editing T-cells

During the 1990s, the Navy lost interest in funding bone marrow transplant research. Dr. June shifted gears, working in infectious disease, specifically on HIV. And, he implemented what he had learned in oncology to infectious disease.

“We showed that we could take the T-cells out from a patient who had AIDS, grow them up in a lab with technology we had developed and then give it back to the same patient, and their T-cell counts got much better. So the immune system started to work where it has been failing,” Dr. June explained. “Our first eureka was when we actually treated those AIDS patients…We saw immediately, their T-cell counts went up, in many cases they doubled and went to normal levels. That was evidence that the CAR T-cells could go into the patients and stay, and actually survive, start dividing. So, that was what we were hoping for, and it worked better than we thought it would.”

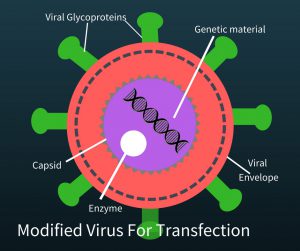

He learned a lot about the virus that causes AIDs. “If you can work in different fields, seemingly  disparate fields, you can sometimes have lessons that applies in one field to help solve the problem in another field,” Dr. June said. To create a therapy which activates the immune system to attack cancer, you need a way to change T-cells. HIV does something that makes it a very useful tool. It attacks the immune system, specifically T-cells, and alters them genetically. In order to use the virus, researchers removed the genetic material of the virus that sickens people but kept the aspects of the virus that made it a good vehicle to transfer genetic material to a T-cell. The HIV virus without its original genetic material looks like the picture on the left. Now “all” the researchers needed was the new genetic material to put into the the “empty” HIV virus (called a modified virus for transfection) and let the virus do the rest.

disparate fields, you can sometimes have lessons that applies in one field to help solve the problem in another field,” Dr. June said. To create a therapy which activates the immune system to attack cancer, you need a way to change T-cells. HIV does something that makes it a very useful tool. It attacks the immune system, specifically T-cells, and alters them genetically. In order to use the virus, researchers removed the genetic material of the virus that sickens people but kept the aspects of the virus that made it a good vehicle to transfer genetic material to a T-cell. The HIV virus without its original genetic material looks like the picture on the left. Now “all” the researchers needed was the new genetic material to put into the the “empty” HIV virus (called a modified virus for transfection) and let the virus do the rest.

Technique 3: Creating Genetic Material to Put Into T-Cells

By 1999, June had retired from the Navy and joined the faculty of the University of Pennsylvania. There were several groups of investigators around the country working to activate T-cells to attack cancers. For many years, work and experimentation focused on the development of this important part of the puzzle–the “insides” of the new T-cells–and how to change T-cells to make them effective killers of cancer. Dr. Michel Sadelain at Sloan Kettering made incredible inroads in genetically manipulating T-cells in mice that cured cancer. Researchers from NCI, St Jude’s Children’s Hospital, Memorial Sloan Kettering, and others were presenting their ideas and research at conferences.

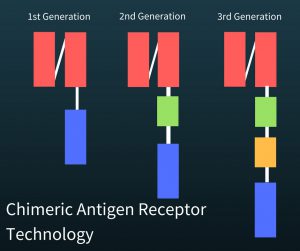

The components of a successful genetically enhanced T-cell involved fitting them with antibodies so that they could recognize cancer cells (red in the figure at right). Additionally there needed to be a part to  activate the T-cell to become a killer T cell (green in figure). Another part (yellow in the figure) has been added to increase proliferation (fewer of the T-cells die and they are more likely to reproduce) of the T-cells and to increase their ability to kill the cancer cells (cytotoxic ability). Finally, a third part of this DNA had to keep the killer T cells going (blue in figure).

activate the T-cell to become a killer T cell (green in figure). Another part (yellow in the figure) has been added to increase proliferation (fewer of the T-cells die and they are more likely to reproduce) of the T-cells and to increase their ability to kill the cancer cells (cytotoxic ability). Finally, a third part of this DNA had to keep the killer T cells going (blue in figure).

Dr. June heard Dr. Dario Campana of St. Jude’s Children’s Hospital present research in 2003, prior to this Dr. Sadelain shared his design with both June and Campana, as well.

The newly created T-cells are called CAR T-cells which stands for chimeric antigen receptor T-cells.

“The word chimera is used because its from Greek word “Chimeric” Beast which is a fusion of two different animals in the Greek mythology. CAR T-cells are a fusion of two cells in the natural immune system. B-cells normally make antibodies, which we use in our defense against viruses and infections. The T-cells normally just kill cells, but does not make antibodies. So a CAR T-cell takes the best world really, of a T-cell and a B-cell.The T-cell can be a killer cell of tumor cells, but also has now antibodies in it, Then that is how we can direct it to kill tumor cells,” Dr. June explained.

Successful Trial in Patients

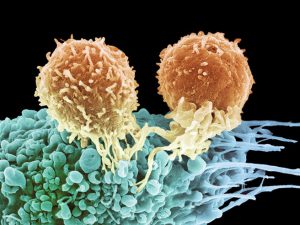

In 2010, Dr. June treated a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) with CAR T-cells containing the chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) designed, developed, and provided by Drs. Dario Campana and Chihaya Imai and others. The case study was published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2011.

“When we treated the first patients with these CAR T-cells, we did not know what would happen. All previous CAR T-cell trials in patients in cancer had failed and not shown any effects. We had all three patients show remarkable remissions. It was so unexpected that [with] patient 1 when the bone marrow biopsy came back with no leukemia I did not believe it. I said, that basically they must have missed it. Leukemia is in the bone marrow, usually they biopsy part of the pelvis, so I just said biopsy the other side and so we did the first biopsy on day 28, and it was negative. And then biopsy on day 31 from the other side came back also normal, with no leukemia. That was astonishing!”

Conclusions

Investigators are working on ways to treat solid cancers like breast cancer, with CAR T-cells. CAR T-cells identify proteins on the surface of cancer cells. Researchers are now creating T-cells that can identify proteins on the insides of cancer cells. Called TCR for T-cell receptor technology, it is another in a series of efforts to create “living drugs” for cancer.

To hear the entire interview with Dr. June, click here.

My question is the following one:

CAR-T Cel therapy for metastatic colon cancer could be successful , in the next future, for patients affected by metastatic colon cancer with peritoneal carcinomas and with the following molecular profile: mKRAS, MSI-satable and MMR-absent?

Thank you so much

Angelo Forgione MD

I’d like to learn more about this while I still can.