Eating Together

For many, being able to commune around a table–talking, laughing and eating–is a sign of health and well-being. That’s why, when someone is sick, and doesn’t eat, conflict can result. Caregivers may feel enormous anxiety, guilt and hopelessness as their loved one loses weight.

is sick, and doesn’t eat, conflict can result. Caregivers may feel enormous anxiety, guilt and hopelessness as their loved one loses weight.

Yet, caregivers need to know what is really happening. Cancer patient, Ann Silberman, in her blog, “Breast Cancer? But Doctor…I hate pink!” explains, “This problem of being unable to eat is not a matter of will-power, nor is it in our [the patient’s] control.”

What is going on?

Cachexia

There is a distinct metabolic disorder, called cachexia, that occurs in people with heart failure (between 16–42%), kidney disease (up to 60%), advanced cancer (as many as 80%), among many other conditions. It is defined as “the loss of 5% or more of body weight over 12 months with reduced muscle strength“…but it is much, much more. Researchers have been discovering changes in the immune system that may be causing this condition. They are looking for ways to treat it.

The Immune System

The immune system is made up of many different types of cells. When there is trauma to the body, pro-inflammatory cytokines are produced by T-cells and macrophages. In healthy people, anti-inflammatory cytokines are also produced, balancing and shutting down the immune system activation once the trauma has been addressed.

The immune system is made up of many different types of cells. When there is trauma to the body, pro-inflammatory cytokines are produced by T-cells and macrophages. In healthy people, anti-inflammatory cytokines are also produced, balancing and shutting down the immune system activation once the trauma has been addressed.

For people with cancer or other conditions, the balance is not maintained. In the case of cancer, cancer cells take over the immune system to produce cytokines that promote tumor growth, tumor survival and tumor spread. Pro-inflammatory cytokines like tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), interleukin-6 and -1 (IL-6/IL-1) and interferon gamma are produced and chronic inflammation occurs. This chronic inflammation is a key force in the development and progression of cachexia and affects the brain, liver, fat and skeletal muscle.

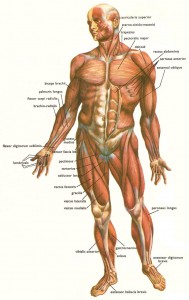

Muscles

The most abundant tissue in the body is skeletal muscle. Loss of muscle mass and muscle strength is a key characteristic of cachexia.

The most abundant tissue in the body is skeletal muscle. Loss of muscle mass and muscle strength is a key characteristic of cachexia.

Muscle that is healthy regenerates after injury and is able to remodel–(a visible example of remodeling is what happens to muscles in people who lift weights). Besides the brain, skeletal muscle takes up and uses much of the glucose in the blood.

There has been research on what happens to muscles in cachexia and the involvement of pro-inflammatory cytokines. For example, muscle proteins break down at a faster rate than before. Replacement proteins are not produced at the same rate. This interferes with muscle regeneration and building of muscles. Another change involves genes. Genes involved in programmed cell death are activated and destroy healthy muscle cells. Third, the mitochondria of the muscles, which are the organelles in the cell involved with energy production, are impacted and do not produce energy effectively. A downward spiral of muscle loss and muscle strength occurs.

And it’s not only skeletal muscles that change. Cardiac muscle, as well as muscles of organs like the stomach, experience these changes.

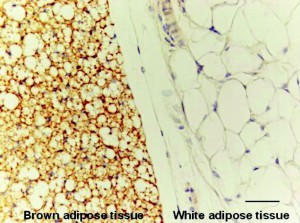

Fat

Another metabolic shift involves adipose or fat cells. For people with cachexia, white fat cells are replaced by brown fat cells. You may have read the popular press touting the benefits of brown fat as in this example from  Women’s Health,

Women’s Health,

“The purpose of brown fat is to burn calories in order to generate heat. That’s why brown fat is often referred to as the “good” fat, since it helps us burn, not store, calories…….Bottom line: You want as much of this type of fat as possible. Bring on the brown!”

Babies and hibernating animals have a lot of brown fat. Brown fat has iron containing mitochondria, multiple fat droplets per cell and more capillaries than white fat. Brown fat has higher oxygen consumption and burns more energy.

Unfortunately, in people with cancer or other chronic conditions, white fat being replaced by brown fat is not a positive sign…this change has been identified as a first step on the road to cachexia. People with cachexia have more fatty acids and glycerols in their blood stream. As yet, the reasons for this change have not been determined although the fact that cancer cells use a different energy pathway than normal cells may be part of the explanation.

Liver

The liver is involved in producing glucose, amino acids, fatty acids and other important building blocks of healthy tissues. As a person’s cachexia progresses, their liver mass increases. Although researchers are convinced that this alteration in size is important, they have not been able to pinpoint the role of the liver in cachexia’s development.

The liver is involved in producing glucose, amino acids, fatty acids and other important building blocks of healthy tissues. As a person’s cachexia progresses, their liver mass increases. Although researchers are convinced that this alteration in size is important, they have not been able to pinpoint the role of the liver in cachexia’s development.

Brain

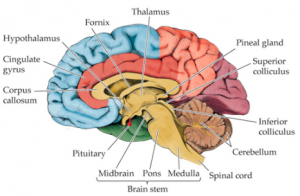

The hypothalamus is a part of the brain involved in food consumption and digestion. One of its duties is stimulating the vagus nerve (which activates and controls the stomach). It is also involved in energy expenditure.

The hypothalamus is a part of the brain involved in food consumption and digestion. One of its duties is stimulating the vagus nerve (which activates and controls the stomach). It is also involved in energy expenditure.

Pro-inflammatory cytokines may impact the hypothalamus, making it less responsive to hormone stimuli causing cachexia’s symptom of reduced or limited appetite. The hypothalamus is also involved in taste. Pro-inflammatory cytokines cause the hypothalamus to increase the sensation of bitterness from the taste buds contributing to people not wanting to eat.

Sickness Behavior

“Sickness behavior” is physical and behavioral change that occurs in people when they have an infection. Caused by the actions of pro-inflammatory cytokines on brain cells, the behaviors include tiredness and fatigue, appetite loss and difficulty concentrating. Anxiety, increased sensitivity to pain and depression are also caused by these cytokines acting on the brain.

Awareness and Understanding

As you can see, cachexia is a complicated condition. Yet, research and treatments are desperately needed. Some believe that if there were some treatment, physicians and other healthcare providers would discuss the condition with patients and caregivers. Perhaps catching cachexia before a patient wastes away, could give patients more time and more options in care.

From A Cancer Patient

Ann Silberman has been experiencing cachexia. She writes

Ann Silberman has been experiencing cachexia. She writes

“you must understand that while they call it is a “loss of appetite,” it is much bigger than that. You may be able to eat when you aren’t hungry – we [patients with cachexia] can’t….It is a symptom, a complication of our disease, same as a runny nose caused by a cold. Pleading with us to eat is like begging somebody with a cold to stop their nose from running.”

Her plea to caregivers,

“I want you [caregivers] to understand that it isn’t their [the patient’s]fault. And it isn’t YOUR [caregiver’s] fault. You can’t make somebody eat, and here is what you must understand – they can’t make themselves eat.

It’s distressing for all involved. I know it is hard for you to watch. You want so badly for us to get healthy and survive longer and we know that. Remember, it is hard for us too. We want all that too, and have the added burden of knowing our loved ones don’t understand, and think we aren’t trying hard enough.”

I believe I have a similar condition, but 3 doctors have said its all in my head!

I have a similar experience but 3 doctors said it all in your head. What gene causes this condition

Hi Mary,

Research indicates that cachexia is caused by the immune system–a problem of inflammation and an imbalance in the pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines in your body. Perhaps you might share this post with your physician. Thank you for your comment.

Could this be the cause of my husband who has dementia but still eats well losing so much weight over the last year?